A step towards First Nations justice in child protection

A Koori-designed program in the Children’s Court of Victoria is providing a more effective and just response for Koori families.

- SVA Consulting recently conducted an independent evaluation of Marram-Ngala Ganbu – a Koori-designed hearing day at the Family Division of the Children’s Court of Victoria. The program is a step towards a self-determining approach to child protection.

- The evaluation was conducted by SVA Consulting, in a team led by Professor Kerry Arabena, a proud Meriam woman of the Torres Strait, with contributions from Dr Wendy Bunston, an expert in child-led practice.

- The evaluation found the program is providing a more effective, culturally appropriate and just response for Koori families through an adapted court process, that enables greater participation by family members and more culturally-informed decision-making. It has transformed the court experience for Koori children and families and is leading to more families staying together.

- Its success is attributable to the leadership, determination and common-sense approach of the Koori man who designed the program with the community, and the innovative and open-minded magistrates who provided the space for things to be done differently.

- It also demonstrates the importance of providing space for and investing in First Nations-led innovation and approaches to social service delivery. The model has potential for expansion across Victoria, and Australia more broadly.

Australia has consistently failed to provide a justice system that supports and strengthens First Nations families and communities. The Marram-Ngala Ganbu program is a standout example of an approach that does, and has transformed the court experience for Koori families and children.

In this article we share the key findings of an evaluation of Marram-Ngala Ganbu, a pilot program that aims to improve outcomes for Koori children and families involved in child protection proceedings in north-east Melbourne. We share the important story of why the program came to be, what is unique about its approach, and the impact it is having on Koori children and families. We also outline how the evaluation was conducted and call for the program to be expanded.

It is timely to share this effective First Nations-led model which demonstrates the importance of providing space for, and investing in First Nations-led innovation and approaches. Such approaches have the potential to not only transform First Nations Peoples’ experience of the justice system, but provide lessons for social services more broadly.

Terminology

In this article, the term Koori people is used to refer to the First Nations people and their descendants who reside and demonstrate an enduring connection to the lands, waters and oceans of the state referred to as Victoria in Australia. Aboriginal people refers to the First Nations Peoples who belong to or who are descendent of the First Nations people on mainland Australia and who reside in the state of Victoria, on the lands of Koori people. First Nations Peoples is used to refer to the indigenous peoples of any nation, such as New Zealand, Canada and the United States of America.

The need for a different approach to child protection for Koori families

As stated in Always Was, Always Will be Koori Children: ‘ Most Victorian Aboriginal children are cared for in loving families, where they are cherished, protected and nurtured, where their connection to community and culture is strong, their Koori identity is affirmed and they are thriving, empowered and safe.’1

Marram-Ngala Ganbu, which means ‘we are one’ in the Woiwurrung language, was established in acknowledgement of this fact. It is an innovative response to the over-representation of Aboriginal children and families in the child protection system in Victoria and funded by Court Services Victoria.

In March 2019, 19.1% of Aboriginal children in Victoria were involved with child protection, compared to 1.4% of non-Indigenous children.2 Further, Aboriginal children in Victoria are 16.4 times more likely to be removed from their families than non-Indigenous children, the second highest over-representation of any state in Australia. The individual, family, and community effects of child removal cannot be understated. This situation has been described as another stolen generation, and numerous reviews and forums have called for a different approach.3

A Koori-designed and -led approach

Marram-Ngala Ganbu is a hearing day at the Family Division of the Children’s Court of Victoria, in Broadmeadows, in north-east Melbourne. It was developed and launched in 2016, via a Koori-led and designed process.

“We needed to make sure that the court had access to the right information about these families to make the right decisions.”

Ashley Morris, who led the process and now coordinates Marram-Ngala Ganbu, was just 24 when tasked with the job. His consultations with the local Koori community, including Aboriginal Community Controlled service organisations, as well as stakeholders in the child protection system informed the process. The result was a number of common-sense changes and other adaptations to the way the court was run that have transformed the experience for Koori children and families. Since its launch, over 450 Koori families have been through Marram-Ngala Ganbu.

As Morris explained, when thinking about the design of the Court process, “I was looking at the culture of the court, and the culture of Aboriginal families… and looking at the conflict. We needed to make sure that the court had access to the right information about these families to make the right decisions.”

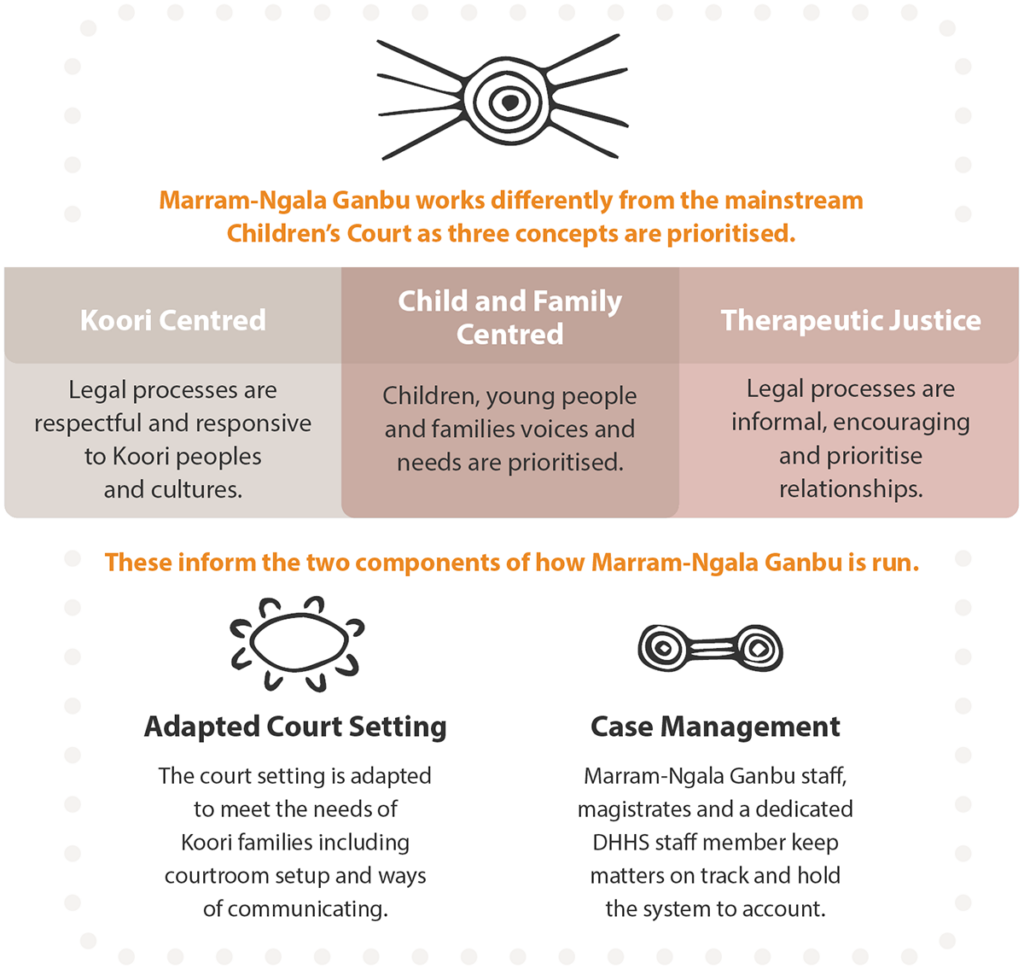

The Marram-Ngala Ganbu approach demonstrates a deep commitment to Aboriginal self-determination through changes to the traditional court set-up and functioning, as well as other innovative approaches to enable the court to be more welcoming and culturally safe for Koori families. The key elements of Marram-Ngala Ganbu are outlined below, through three core concepts and two delivery components.

The illustration at the top represents Marram-Ngala Ganbu, and symbolises Aboriginal men and women on a journey path (lines), coming to meet (circles), and preparing to make decisions. The Adapted Court Setting symbol represents people sitting and talking. Here, it symbolises families, courts and services coming together to make important decisions for families. The Case Management symbol represents a travelling and resting place. Here, it symbolises the journey of families as they are supported through the case management approach.

Koori-centred

Several elements of Marram-Ngala Ganbu demonstrate Koori-centred approaches to jurisprudence. While Koori-centred approaches have been a feature of criminal courts across Australia for some time, their application in a child protection setting is less common, with very few examples in Australia or overseas. The key features of Marram Ngala Ganbu are:

- Koori staff led the design, implementation and day-to-day function of the program. The design process was a material ‘power shift’ that translated into the day-to-day operation of the program.

- Staff in the court have a high level of cultural competence. Magistrates and court staff ensure that processes and decisions respond to the importance of Aboriginal culture in child protection.

- Marram-Ngala Ganbu provides a culturally safe environment for Koori families. The court setting features multiple physical and verbal acknowledgements of culture, all of which were identified as critical to cultural safety by participants interviewed for the evaluation.

- Marram-Ngala Ganbu provides warm referrals to a range of Aboriginal-controlled support services in the region. The evaluation identified these too were important in providing cultural safety and contributed to better outcomes for families and young people.

“You need to be across all those issues, when you are sitting that close to families, and you feel the intensity of the legacy of the stolen generation.”

“My awareness of culture, of the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle, has absolutely been heightened as a result of Marram-Ngala Ganbu,” said one of the magistrates. “You need to be across all those issues, when you are sitting that close to families, and you feel the intensity of the legacy of the stolen generation.”

Case study: The role of Marram-Ngala Ganbu facilitating reunification

Sally is a non-Aboriginal mother of three children aged 15-18 years old who identify as Aboriginal. The family was involved in the mainstream Children’s Court prior to moving to Marram-Ngala Ganbu, and all three of the children were on Care by Secretary orders.7

Marram-Ngala Ganbu provided a space for Sally and her children to speak directly to the magistrates and access the support they needed for reunification to be an option inside and outside court, such as explaining court reports, support during DHHS home inspections, and help to re-engage the children in more appropriate schools that better met their learning needs.

After more than two years of being separated from her children, through Marram-Ngala Ganbu, Sally was able to regain custody. At the time of the evaluation, Sally and her children were still living together. In Sally’s words, “When the Magistrate decided to speak with my children on their own it made me cry because no other judge would do that.”

Therapeutic justice

Marram-Ngala Ganbu promotes therapeutic judicial practice that is child-centred and less adversarial, by enabling children and families to engage with the legal process and have an opportunity to have their say. Therapeutic justice focuses on the ‘healing potential’ of the law, acknowledging that the legal process itself can affect the wellbeing of people and be a positive or negative contributor to the goals of the justice process. This approach has been demonstrated to lead to improved outcomes in courts across the world.4

In Marram-Ngala Ganbu, this happens through the informal nature of hearings, which invite everyone sitting at the table to speak freely to the Magistrate in a conversational manner, including families and children. What’s more, fewer cases are heard on a Marram-Ngala Ganbu court day than in mainstream court, allowing more time for each hearing. Hearings are also conducted in a way that is more collaborative, by encouraging those in attendance to work together to find mutually agreeable solutions, and placing high value on decisions reached in Aboriginal Family-Led Decision Making meetings and conciliation conferences.

Child and family-centred

At the core of the practices described above are the families and children that participate in Marram-Ngala Ganbu. Providing emotional and practical support to families is key. So too is empowering children and families, by providing them the opportunity to speak to one another, to magistrates, and to the department responsible for child protection in Victoria (the Department of Health and Human Services, or DHHS) – about the history of their case, their circumstances and what they want to happen in their child protection matter.

“… to be treated like that by an actual judge who doesn’t see us as just foster kids… It came as a shock to all of us that she wanted to speak with us, like we were privileged.”

Marram-Ngala Ganbu also recognises the role of extended family in the lives of the children, and actively encourages families to bring Elders and other people from the community to provide support and input to hearings. As well, Marram-Ngala Ganbu operates from a core belief that parents want the best for their children, and that families should be afforded the opportunity and support required for family reunification (if possible).

One young Koori participant described her experience: “She [the Magistrate] just wanted to put the lawyers away and DHHS and the parents and just talk to us kids… She was really nice and really calm and just treating us like equals… I was 14-15 years old and to be treated like that by an actual judge who doesn’t see us as just foster kids… It came as a shock to all of us that she wanted to speak with us, like we were privileged.”

Adapted court setting

Core to Marram-Ngala Ganbu is the adapted court room setting. This includes:

- Culturally affirming environment: The Court room features Aboriginal artwork and maps, and a written and verbal acknowledgment of country and stolen generations. At the table’s centre is a possum-skin cloak (created by Koori children from the region), topped with a coolamon (an Aboriginal carrying vessel) filled with fresh gum leaves. This creates a warm and familiar environment.

- Unstructured and flexible: A maximum of 10 cases per day allow more time for each matter.

- Inclusive: Extended family and children welcome to attend. Everybody present is invited to introduce themselves and their connection to the family.

- Informative and accessible: All parties sit around a round table. The Magistrate speaks directly to parties and explains process and information in simple terms, and encourages parents through positive feedback and recognition of progress.

- Adherence: Strict adherence to Aboriginal Child Placement Principle ensures children are only removed from their family as a last resort, and are placed with next of kin wherever possible.5

Case management approach

A case management approach led through a partnership of Marram-Ngala Ganbu staff and a dedicated Marram-Ngala Ganbu DHHS staff member provides oversight on each court case and ensures they continue to progress. This includes ensuring families and DHHS are prepared for cases to be heard on court hearing days, and that court orders are followed-up. The use of case docketing (requiring that cases and court orders are managed consistently by one magistrate as they progress) also ensures that magistrates are familiar with the details of each case.

“Any worries and concerns with the stress leading up to Court I could get in contact with the support workers and it makes a whole lot of difference.”

Evaluation finds Koori experience of court transformed

The evaluation found the court experience for Koori families and children has been transformed by Marram-Ngala Ganbu, successfully encouraging Aboriginal people to feel welcome, heard and empowered. Simple changes made to the court room and process had a dramatic effect – including offering support before, during and after court from Koori staff who built relationships with families and into the community.

As one Koori parent who participated said: “Any worries and concerns with the stress leading up to Court I could get in contact with the support workers and it makes a whole lot of difference. I was excited going to [Marram-Ngala Ganbu] because of the fairness.”

“My voice was heard, and my children’s voice was heard. Other courts people are speaking for you and it’s frustrating.”

The evaluation found the program is providing a more effective, culturally appropriate and just response for Koori families through the adapted court process, that enables greater participation by family members and more culturally-informed decision-making.

Another Koori parent said: “I was able to be heard and was able to speak. My voice was heard, and my children’s voice was heard. Other courts people are speaking for you and it’s frustrating.”

Koori families are more likely to attend court at Marram-Ngala Ganbu, and more likely to follow court orders due to the support of the magistrates and Koori staff. Also, DHHS is more accountable to magistrates and the court process in Marram-Ngala Ganbu. There is greater compliance with the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle, which is otherwise not being well adhered to in courts across Victoria according to a 2016 review.6

“Marram-Ngala Ganbu… has obliged DHHS [Government] to take a fresh look at the case and held them accountable for their decisions, the children go home.”

There are also early indicators that more families are staying together and having their children returned from the care of government (known as Care by Secretary Orders).7

A lawyer who has participated in Marram-Ngala Ganbu said: “I’ve seen outcomes that are surprisingly positive. For example cases where children are on Care by Secretary Orders and have been out of parental care for years but because Marram-Ngala Ganbu has encouraged families to participate and created a culturally appropriate space and has obliged DHHS [Government] to take a fresh look at the case and held them accountable for their decisions, the children go home.”

The program is also likely to lead to savings to government when children are diverted out of the child protection system or spend less time in the system as a result of Marram-Ngala Ganbu. The average cost per child of providing out-of-home-care services in Victoria in 2018-19 was nearly $68,000 for the year.

Children who spend time in out-of-home-care are also more likely to enter the criminal justice system, develop substance dependencies, experience homelessness, and be hospitalised which incur further cost to government. In time, government may expect to avoid these future costs, as there are early signs that families are more likely to stay together as a result of Marram-Ngala Ganbu. These savings are further outlined in the full evaluation report.

About the evaluation

The evaluation was conducted in 2019 by SVA Consulting, in a team led by Professor Kerry Arabena, a proud Meriam woman of the Torres Strait, with contributions from Dr Wendy Bunston, an expert in child-led practice.

Research involved a mixed-methods approach, including qualitative and quantitative analysis, grounded in a theory of change. Court data was analysed. Thirty Koori adults and young people were also interviewed to understand the impact of the program, as well as 30 people from other organisations involved in Marram-Ngala Ganbu. Interviews were trauma-informed, and culturally safe. This was achieved by conducting interviews in a familiar space (at a local Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation), with supports available. Interviewers were the same sex as participants wherever requested and led by Aboriginal team members where possible. Ethics approval was acquired from the Justice Human Research Ethics Committee with support from the Koori Justice Unit.

What next?

Marram-Ngala Ganbu is a step on the journey towards a more self-determining approach to First Nations justice in the child protection system. This evaluation demonstrates how putting culture at the centre of the Children’s Court process, amongst other changes, has led to substantial improvements in the experience of Koori families. This in turn leads to more families staying together.

“We’ve tried your system and it isn’t working. We can’t yet have our own – talks for treaty are still underway. So let’s meet in the middle, and bridge that gap until we are ready.”

Marram-Ngala Ganbu also demonstrates the importance of providing space for, and investing in First Nations-led innovation and approaches to social service delivery. The success of Marram-Ngala Ganbu can be largely attributed to Morris, its first coordinator, who brought strong leadership, determination, and common sense to his role in designing and delivering the program.

“We’ve tried your system and it isn’t working,” said Morris. “We can’t yet have our own – talks for treaty are still underway. So let’s meet in the middle, and bridge that gap until we are ready… this will do for now. We’ve proven that it’s working in the way child protection matters are dealt with for Aboriginal families.”

Importantly, magistrates with a willingness and commitment to do things differently also enabled the program. It will take a similar approach and commitment to enable Marram-Ngala Ganbu to be expanded across Victoria and to ensure it has the best chance of continuing success.

Approaches like Marram-Ngala Ganbu have the potential to not only transform First Nations Peoples’ experience of the justice system but have lessons for social services more broadly. SVA joins those voices, including the Aboriginal Justice Forum and Aboriginal Justice Caucus, calling for the expansion of the program.

Author: Doug Hume

Contributors: Desmond Campbell, Susie King and Kate Eccles

The evaluation was prepared by a team led by Professor Kerry Arabena, together with an SVA team comprising Susie King, Desmond Campbell, Doug Hume, Kate Eccles and Nancy Tran, with contributions from Dr Wendy Bunston.

Names of participants have been changed to avoid the identification of the families.

1 Always Was, Always Will be Koori Children, Report of Taskforce 1000 (October 2016)

2 SNAICC (2019), The Family Matters Report 2019

3 The concept of Marram-Ngala Ganbu was first proposed in 2009 as a recommendation of the Aboriginal Justice Forum (#23). In 2012, the Report of the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry also recommended the program be developed, as have numerous reviews and forums since, outlined in the report.

4 As detailed in Wexler, David B. and Winick, Bruce J. (2008), Therapeutic Jurisprudence. Therapeutic Jurisprudence, in Principles of Addiction Medicine, 4th Edition. See full evaluation report for further examples and references.

5 The Aboriginal Child Placement Principle is to ensure that ‘Aboriginal children and young people are maintained within their own biological family, extended family, local Aboriginal community, wider Aboriginal community and their Aboriginal culture’. They are only to be removed from their family as a last resort.

6 Report of the Aboriginal Commissioner for Children and Young People, In the Child’s Best Interests, 2016.

7 A Care by Secretary Order confers parental responsibility for a child to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, to the exclusion of all other persons. It is in force for a period of two years, unless the child turns 18 or marries (whichever occurs first).

8 Photo credit for image of Ashley Morris and Magistrate Kay Macpherson: Simon Ward, Australian Story, ABC.