A how-to guide for NFP mergers: from idea to implementation

A how-to guide for not-for-profit (NFP) organisations exploring mergers, with insights from our work supporting organisations on their merger journey.

- Mergers can be more impactful when organisations invest in early alignment, design and planning.

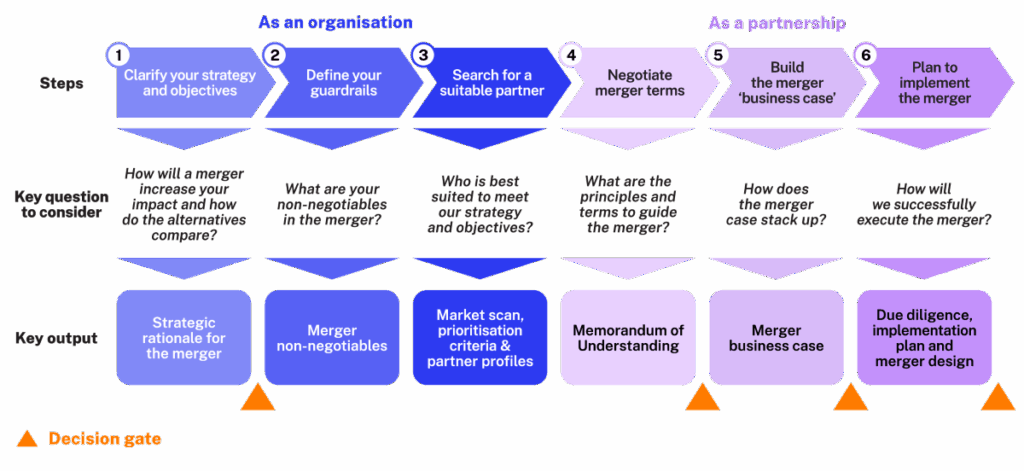

- This article sets out six key steps from merger ideation to implementation: three of these steps to be done as an individual organisation and three with your potential partner.

- Each step involves a clear objective, with what’s needed to inform whether to continue the merger process.

- Insights and examples highlight the importance of undertaking each step carefully to set your merger up for success.

Merger discussions are on the rise in the sector.1 Whether it be for enhanced capability or capacity, driving improved financial health, or building a stronger advocacy position – NFPs are increasingly seeing mergers as an important strategic option to increase or sustain impact.2 While mergers can require substantial effort including board and leadership time and costs for external supports, they can be incredibly impactful when successful.3

This article shares SVA’s tried and tested framework for merger planning.4

Six steps from idea to implementation

SVA recommends six structured steps for merger planning – each with key questions, considerations and outputs.

As an organisation, individually:

1. Clarify your strategy and objectives

2. Define your guardrails

3. Search for a suitable partner

As a partnership, with the potential merger organisation:

4. Negotiate merger terms

5. Build the merger ‘business case’

6. Plan to implement the merger.

This process includes decision gates for whether to proceed, to minimise wasted effort. As you progress, there is an increase in the resourcing and effort needed, alongside the breadth of stakeholders you need to engage with.

Organisations often jump straight to step 5, possibly because they have already connected with a potential partner, or even already started discussions. However, it is critical to consider steps 1-4 as these will provide the objectives, non-negotiables and terms to guide the merger planning in steps 5-6.

Steps 1-3: conducted as an individual organisation

1. Clarify your strategy and merger objectives

How will a merger increase your impact and how do the alternatives compare?

Why is this important?

Before progressing with a merger, be clear about why you are doing it (how it will increase your impact) and ensure that this is the best way to do that (i.e. there are no better strategic options). This will guide you along your merger journey, anchoring your search for partners, directing your business case, and providing a narrative to stakeholders.

What to consider

Ask the following questions:

- What impact do you create and how?

- How would a merger help increase your impact?

- How do the alternatives compare?

- What would it take to successfully execute?

For more details see The four questions to ask when considering a merger.

What will you develop?

You will have a clearly articulated strategic rationale for your merger: including the core objectives that you hope to achieve; key benefit drivers; and comparison to other strategic options. If a merger is still the preferred option, you are now able to consider your merger guardrails.

Insights

- Don’t skip this step. Without early clarity on your merger objectives, it is difficult to be certain that a merger is the best option or to target the right merger for your organisation. This step can also minimise staff push-back on a merger where you haven’t first considered internal improvements or other partnership options.

- Focusing on your organisation’s objectives will help keep you focused on the merger’s potential impact- which should be the overriding principle to govern all trade-offs and decision-making.

2. Define your guardrails

What are your non-negotiables in a merger?

Why is this important?

Mergers involve structural changes that may impact your organisation, culture, and ways of working. For many NFPs, there are features that they do not want to lose in a merger.

Before beginning conversations with any partner, you need to be explicit about what is, and is not, on the table. Understanding your non-negotiables will be essential in identifying suitable partners and shortcutting negotiations with them later. These non-negotiables form part the discussions on merger terms in step 5.

What to consider

Guardrails for NFPs vary. They can include protecting the organisation’s mission, retaining the organisational brand, or the composition of the board. Ask yourself, what are the features of how you currently operate that you are not willing to compromise on? What would your key stakeholders be unwilling to accept?

Some common non-negotiables to check are:

- Clients, services, and geographies: Are you open to changes in client, services or geographies served?

- Branding: Are you comfortable with any changes in name or logos?

- Board and leadership team composition: Are you comfortable with losing people from the board and leadership team? Who are you unwilling to lose under any circumstances?

- Redundancies: Are there specific teams who must be retained? How should redundancies occur, if at all?

- Assets and surpluses: How should assets and surpluses created by the merged entity be invested?

Retaining their brand was an essential guardrail for a South Australian homelessness services and housing provider, given its long history in the region and its connection to community.

What will you develop?

You will have a clear list of non-negotiables. With this, you are now ready to search for a partner.

Insights

- Like step 1, organisations often overlook this step. However, non-negotiables inevitably surface in later merger discussions and can lead to a deal falling apart after investing significant resourcing. Worse, if you proceed without protecting your non-negotiables, you risk alienating key stakeholders like funders or vital staff.

3. Search for a suitable partner

Who is best suited to meet our strategy and objectives?

Why is this important?

Investing in the partner search will provide board, leadership and key stakeholders with the confidence that you have assessed the market for the best possible organisation to help increase your impact.

What to consider

Identify potential partners by applying a series of filters, including those based on the objectives identified in step 1. For instance, if one of your objectives is to expand geographically, then a filter could be to screen for organisations operating with the same cohorts and providing the same services but in different jurisdictions. Other potential filters might include size of the organisation, financial health or intangibles such as similarity of mission or perceived cultural match.

House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation (who merged to become Aruma) both individually scanned the market validating that the other organisation was the best partner to achieve their objectives. They had a shared commitment to the human rights of people with disability and delivering superior outcomes. They also had strong values and cultural alignment, both in their existing values and the changes they believed would be needed in the future.5

What will you develop?

You will have profiles of shortlisted organisations and identified a preferred partner to engage in negotiations.

Insights

- Even if a potential partner has already surfaced, scan the market to ensure no opportunities are overlooked and validate the best partner to achieve your objectives. Merger discussions with potential partners can fall through, but with your partner search, you can revert back and identify an alternative organisation.

Steps 4-6: conducted as a partnership

4. Negotiate merger terms

What are the principles and terms to guide the merger?

Why is this important?

This is the first formal step of negotiations between both parties, to align on the joint strategic rationale for the merger and agree merger terms and principles.

This creates early alignment on potential show-stoppers prior to significant investments. It also surfaces what really matters to each organisation in the merger, providing clarity for the focus of the business case and due diligence. When done well, this step strengthens relationships between parties and sets the tone for the merged organisation.

What to consider

Negotiations are often conducted between CEOs and appropriate board members, sometimes with input from senior leaders. The merger terms and topics included varies and are dependent on the organisations, their context, their strategic objectives and the individual guardrails defined in step 2. These terms are typically documented in a straightforward, non-legally binding Memorandum of Understanding, which does not require lawyers to develop.

In the BaptistCare merger, the organisations committed to a principle that they would be a merger of equals with regard to governance matters, and that the merged entity would retain its commitment to the Baptist faith and mission-driven services.

Common topics to align on include:

- Strategic rationale and merger vision: How a merger would increase your joint impact

- Board chair and board members: How future board chair and members will be appointed

- Composition of members: How existing members will or will not shift to the merged entity

- CEO selection: Selection criteria of the future CEO

- Brand and name: Criteria for the merged entity’s brand and name.

What will you develop?

You will have consolidated your merger terms and principles into a Memorandum of Understanding that is signed by key decision-makers from both organisations. Now, you are ready to begin developing the merger business case.

Insights

- Merger terms often cover sensitive topics such as chair and CEO appointments, and composition of the board. It is critical that key decision makers check their ego at the door to focus on what is best for the future merged entity.6

- Allow sufficient time to build relationships and discuss perspectives to avoid missing show-stoppers or clashing over a topic that could have been resolved with more patience and understanding.

5. Build the merger business case

How does the merger case stack up?

Why is this important?

The business case captures the justification for the merger: why it should be done, what it will achieve, and what it will take to get there. It serves several purposes:

- Determine whether the merger is worth the investment

- Create a shared understanding among key stakeholders

- Enable early mitigation of potential risks

- Identify further questions to address before merger approval, including the required time and resources.

What to consider

The topics and level of detail required varies depending on the merger context, objectives and complexity, however there are a few topics that should be captured in any business case:

- Strategic rationale and merger vision (see step 4)

- Impact on end beneficiaries

- Financial costs and benefits

- Staff, stakeholder, legal, and tax considerations

- Risks and mitigation

- Implementation plan, including resource requirements and costs.

In the House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation merger, scenario analyses were run on the business case to determine the best- and worst-case scenarios in terms of impact, costs and risks. These later served as the basis of merger planning and value capture.

What will you develop?

You will have a comprehensive business case with sufficient information to convince both boards and relevant stakeholders of the merger’s value. This is typically when boards provide ‘in principle approval’ to merge, i.e., if there are no red flags or complications (such as stakeholder approvals), the merger will proceed.

Insights

- As the level of rigour and detail in the business case is largely dependent on the boards’ needs, it is important they are engaged early to clarify the topics and questions most pertinent to them. This becomes the ‘burden of proof’.

- The business case must detail why the merger is better for beneficiaries. This requires effort to understand what beneficiaries need, and why the merger will meet those needs. There is little point in reaching more beneficiaries if current services are subpar.

- Given the breadth of the business case, this step requires input from a range of staff from both organisations, including finance, human resources, risk, legal, operations and service areas. Allocate sufficient resourcing to draw on this staff knowledge to develop the business case.

- It is often valuable to engage an external party to support this step, both to tap into capabilities and capacity that NFPs often lack internally, and to provide an independent perspective to the boards.

6. Plan to implement the merger

How will we successfully execute the merger?

Why is this important?

Once the business case is approved, the next step is to conduct due diligence, implementation planning and design the merger.

- Due diligence: Helps protect you from surprises and identifies any problematic issues with the other organisation that would lead you to not proceed with the merger

- Implementation planning: Ensures there is a roadmap with milestones, agreed timelines and adequate resourcing to execute the merger effectively and on time

- Merger design: Can give clarification and confidence to boards and key stakeholders and sets the organisations up for implementation.

What to consider

Due diligence: Due diligence is the evaluation of any elements that are ‘material’ to whether a merger should proceed, and can occur prior to implementation planning and merger design. The level of due diligence depends on the risk appetite of each organisation and ensures board members have fulfilled their fiduciary duties. Relevant topics include:

- Potential legal disputes or regulatory issues

- Change in control clauses that may have a financial impact on the merged organisation7

- Employee issues, including industrial relations disputes

- IT roadmaps or system upgrades that are in train, which may require significant changes.

Implementation planning: This typically covers what is required up until day one of the merger, the first 12 months of the merged organisation, and at least a high-level plan for the following years until integration.

Merger design: Some elements are critical to design prior to merging, and others can be designed afterwards, depending on the context.

At a minimum, the following items should be clarified to approve and effect a merger:

- Legal structure: Typically, a merger is structured as an acquisition, either by one of the organisations or by a parent entity. This can entail change of control, transfer of assets or changes to constitutions.

- Member approval (for member-based organisations): How will member approval be secured? If the intent is to establish parent and subsidiary entities, all members of subsidiaries must resign with the new parent becoming their sole member.

- Board and leadership selection: What will be the key leadership roles and how will those roles be filled?

- Stakeholder engagement: What are the communication plans for beneficiaries, staff, members, regulatory bodies and funders? Do any need to be engaged by the leadership teams prior to merger approval?

- Operating model, value capture, and business integration: Operating model, value capture plans and full integration could be designed prior to day one of the merger or could be left until after transaction close, depending on the context and board preferences.

What will you develop?

You will have a due diligence report identifying anything significant that could stop the merger from proceeding, an appropriate implementation plan and merger design. If there are no issues in due diligence, then both organisations will typically unconditionally approve the merger.

Insights

- Whether due diligence is an intensive or straightforward process depends on the organisations. It is crucial that both boards are explicit about their risk appetite and potential merger concerns.

- This is the time to begin allocating significant internal resources. This may involve assigning certain staff to merger implementation, with others focussed on day-to-day service delivery.

- Most NFPs will not have the internal capabilities and capacity to deliver on the merger planning and implementation. Get the right external partners who can provide quality support to set the merger up for success.

- It is critical to involve the right stakeholders early. Establish a clear plan for when and who will engage which stakeholders and the appropriate messaging.

Conclusion

Mergers can be incredibly impactful, but they require investment in early alignment, design and planning. With a clear process, decision gates and consideration of the right elements, a merger can amplify the collective impact of both organisations.

Look out for further articles this year with reflections from NFP organisations on their merger journey. Subscibe to the Quarterly.

1. Australian Institute of Company Directors, Yearly Not-for-Profit Governance & Performance Study, 2015-2024, Australian Institute of Company Directors, accessed 26 February 2025.

2. I Bonte, D Roy, The four questions to ask when considering a merger, SVA Quarterly, April 2025

3. D Haider, K Cooper, R Maktoufi, Mergers as a strategy for success, Metropolitan Chicago Nonprofit Merger Research Project, 2016, accessed 27 February 2025. Findings based on analysis of 25 NFP mergers between 2004 and 2014 in the region.

4 & 5 D Ferner, M Garrow, How to go about a non-profit merger, SVA Quarterly, March 2018

6 M Garrow, Mergers and acquisitions: four things for boards to keep top of mind, SVA Quarterly, October 2019.

7 Change of control clauses are sometimes included in contracts, including funding contracts and services agreements. Where the control of the organisation changes, that contract may be terminated or require renegotiation.