How to go about a non-profit merger

A how-to guide for non-profit organisations seeking to explore whether a merger is right for them, with insights and lessons learned from a recent large-scale merger in the disability sector.

- Mergers can be a powerful strategic option for organisations to do more for the people they serve.

- However, mergers are risky so it is critical to be clear on why a merger is better for end beneficiaries.

- This article shares insights from the recent merger of House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation which SVA helped facilitate.

When Andrew Richardson, CEO and Managing Director of House with No Steps, and Graeme Kelly, CEO of The Tipping Foundation, first discussed the possibility of a merger, they were both clear on one thing: status quo was not an option if they wanted to continue maximising impact for the people they serve.

Both disability services providers knew they needed to transform… in response to changing dynamics in the disability sector.

Both disability services providers knew they needed to transform – and transform effectively and efficiently – in response to changing dynamics in the disability sector. But was a large-scale merger the right avenue for transformation? And if so, how should they proceed to achieve the best possible outcome for their customers?

This article provides a how-to guide and lessons learned for non-profit organisations seeking to explore whether a merger is right for them and if so, how to go about such an arrangement. For simplicity, we use the term ‘merger’ in the article to refer to both mergers and acquisitions and provide insights on those specific arrangements, however the framework presented below can apply equally to other forms of collaboration (e.g. joint venture) as well.

This article focuses primarily on large-scale, game-changing mergers with some guidance for smaller roll-ups as well. Our recent experience supporting House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation to merge acts as a case study. Together, the organisations form Australia’s largest disabilities-focused provider with around 5,000 staff servicing 5,000 customers throughout eastern Australia and over $300 million in revenue.

Mergers on the rise

The introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has created both a challenge and opportunity for organisations to do more for people with disability. In response, disability services providers are increasingly exploring the possibility of merging. The National Disability Services (NDS), a peak body for disability services providers, reports that 38% of organisations are currently discussing a merger, with 7% currently undertaking a merger.[1]

This past year alone, the sector has seen a flurry of mergers, including those between Civic Disability Services and Rec Ability, Southern Way and STAY, Life Without Barriers and DUO Services, and Care Options, Community First International, and Volunteer Task Force. Additionally, the New South Wales Government’s Department of Family and Community Services (FACS) has transferred disability services to the non-government sector and the Victoria State Government’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) is in the process of divesting its disability services as well.

it is critical to get clear on why it is that a merger is better for end beneficiaries.

Typical rhetoric around non-profit mergers in the past suggests that mergers were often being pursued as a last resort (e.g., due to financial distress). However organisations are increasingly recognising mergers as a potential strategic option to turbo-charge the ability to do more for end beneficiaries. For instance, mergers can enable organisations to invest jointly to improve or innovate their services, share knowledge and intellectual property, expand their geographic reach, or present a joint case to government, funders, or donors.

There is enormous potential to use a merger to deliver better outcomes for end beneficiaries and indeed, the [SVA Fundamentals for Impact] identifies collaboration as a key characteristic of highly impactful organisations.

However, mergers are also risky. Organisations need to ask themselves: are there are other less risky options that could achieve the same objectives?

Studies in the corporate sector have found that roughly 1 in 3 mergers create value with roughly another 1 in 3 actively destroying value.[2] As a result, it is critical to get clear on why it is that a merger is better for end beneficiaries – what we call the strategic rationale and ‘business case’ for a merger. When it comes to non-profit mergers, the question ultimately boils down to why is it that a merger is the best option to achieve improved outcomes for end beneficiaries? (Note that unlike in the corporate sector, there is no ‘purchase price’.)

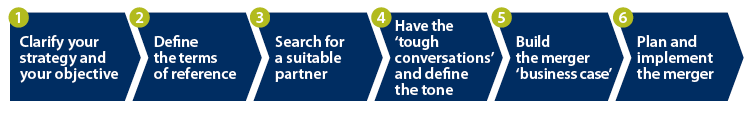

A framework for a merger

Drawing on our experience, including most recently with House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation, SVA Consulting has developed a simple framework to assist non-profit organisations considering a merger as a potential strategic option to enhance their impact. As previously mentioned, this framework can be adapted to other forms of collaboration as well.

1. Clarify your strategy and your objective

Before exploring any merger, an organisation should first seek to clarify its strategy and objectives, and then consider whether those objectives might be best achieved by a merger or another alternative.

Common objectives and options for achieving those objectives include:

- Broaden impact by reaching more people or extending services – Which cohorts, geographies, or services would be complementary to existing services? Can growth be achieved through organic growth, referral partnerships, or a joint venture? Or is a merger the best option to facilitate the size and speed of growth desired? Of course, this assumes there is evidence that the core service delivery is already achieving superior outcomes, and that there is a desire and opportunity to extend that to more people.

- Strengthen or innovate practice – What practices need to be strengthened? Has a research partnership been considered or is there intellectual property belonging to a specific partner that is required? Is there benefit in sharing the risk with another party and leveraging the other party’s knowledge and balance sheet?

- Improve operational efficiency – Are there potential efficiency gains to be had in back office (e.g. finance, HR, property, fleet, IT, procurement) or service delivery (e.g. staff deployment)? For back office, has the creation of a management services office to share back office with other organisations been considered? For service delivery, are there new technologies or ways of working that can achieve improved efficiencies? Or is there a reason why a full merger makes the most sense?

- Present a joint case to government, funders, and donors – Is there a more compelling case to government, funders, or donors that can be made by offering complementary services, tapping into local knowledge or specific expertise, or reducing funder or donor fatigue? Has a joint venture or specific partnership around fundraising been considered, or are there other reasons why a merger would deliver long-term, sustained benefits?

- Catalyse an opportunity to start blank slate – Could a new strategy, brand refresh, etc. be used as a platform for starting fresh, or would it take something like a merger to really signal change?

… together, we knew we could achieve all these objectives faster and more effectively.

House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation saw a merger as creating the potential to both deepen and broaden their impact.

As Richardson says, “Together, we could invest and share resources to ensure quality and consistency of service delivery; attract, develop, and retain great staff. We could also implement new technologies to make it easier to engage with us and the NDIS easier to navigate.”

A merger would also broaden and cement the organisations’ footprint in eastern Australia, with services throughout Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and the Australian Capital Territory.

“Individually, we could achieve these objectives to varying levels of success,” says Richardson. “But together, we knew we could achieve all these objectives faster and more effectively.”

If, after clarifying and testing the objectives, a merger looks like the best option to proceed, the next step is to define the terms of reference.

2. Define the terms of reference

Before engaging with another party, taking the time to discuss and define the terms of reference of a merger with the board up front helps ensure alignment on what is or is not on the table. It also defines the guardrails for what a potential partner or merger could look like. Is everything on the table or are there constraints on what would be acceptable? For instance, is there openness to changing brand? Are there strong views on how the new board or leadership team might be selected? It is important to probe for specifics where possible. For instance, a principle like equality could mean equal board representation, equal leadership representation, and/or equal member representation. What does equality really mean?

The terms of reference will inform the basis of subsequent discussions on non-negotiables with potential partner organisations (see ‘4. Have the ‘tough conversations’ and define the tone’).

Mergers often require significant resources, and it may also be worth considering at this stage who and what resources are available to support a merger effort, acknowledging that the resources required may increase over time if a suitable merger partner is found and if the merger is approved.

3. Search for a suitable partner

Even if a potential partner has already been identified, as was the case for House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation, it is important to scan the whole market to ensure no opportunities are overlooked and to identify or validate the best partner to achieve the objectives. This applies equally to acquisitions motivated by one organisation’s financial distress. For the organisation experiencing financial distress, which organisation will best protect and enhance outcomes for end beneficiaries? For organisations looking to acquire, is the target organisation a good fit with broader organisational objectives?

It can be helpful to identify potential partners applying a series of filters, including filters based on the objectives identified previously. For instance, if an objective is to reach more people or extend services, a reasonable filter is to screen for only organisations operating in the cohorts, geographies, or services that complement existing services. Other potential filters might include size of organisation, type of disability focus, whether they are solely focused on disability, or intangibles such as similarity of mission or perception of cultural match.

They… had a strong values and cultural alignment, both in their existing values and the changes they believe would be needed in the future.

For House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation, scanning the market and validating that the other organisation was the best partner to achieve their objectives was critical to building confidence in a potential merger. Among other reasons, they were both deeply committed to upholding the human rights of people with disability and delivering superior outcomes for their customers, and had a strong values and cultural alignment, both in their existing values and the changes they believe would be needed in the future.

4. Have the ‘tough conversations’ and define the tone

Any merger, even a ‘simple’ one, takes significant time and effort. Anecdotal evidence suggests there are many instances of non-profit mergers falling through at the last minute over a disagreement on something like branding.

Getting clear on non-negotiables, defining and agreeing key merger principles, and checking for potential show-stoppers early with a partner is a good way to do a quick check for potential deal breakers. Plus, this builds some trust before investing too much time and effort into exploring a merger. We have also found that it can be a good way to set the tone and culture of the merger moving forward.

Kelly reflects, “The definition and face-to-face prosecution of a set of explicit merger principles was very important. It was very much the case, particularly when the discussion got tougher and helped avoid potential diversion, derailment, and unwelcome surprises.”

Non-negotiables

Some common non-negotiables to check are:

- Clients, services, and geographies – Are both organisations open to changes in client groups served, services provided, or geographies served?

- Branding – Are both organisations comfortable with any changes in name, logos, colours, or anything else that may occur as a part of a merger?

- Board composition – Are there strong views on how the future merged entity’s board should be composed? How directors should be chosen?

- Leadership – Are there strong views on who should be in key positions of leadership?

- Assets and surpluses – How should assets and surpluses created by the merged entity be invested? Is it up to the future merged entity to decide or does a specific portion need to be earmarked to a certain cohort, service, or geography?

- Redundancies – How should redundancies occur, if at all? Are there employees or teams who must be retained?

- An independent facilitator can often be helpful to ask the tough questions and facilitate discussions on non-negotiables.

Everything was on the table so long as it could be established that something was better for customers.

Key merger principles

It is equally important in the early stages of merger talks to identify any shared principles to guide a potential merger. For instance, one key principle identified by House with No Steps and the Tipping Foundation was that everything would be guided by what is best for customers. Everything was on the table so long as it could be established that something was better for customers.

This set the tone for a partnership focused on driving better outcomes for customers and united the organisations in the pursuit of a common goal.

Potential show-stoppers

Finally, organisations considering a merger would do well to check for potential show-stoppers early. Potential show-stoppers include:

- Funding – Are there any major funding contracts that might be lost if a merger were to go through? Are there any major donors or bequests that could be at risk?

- Legal and tax – Are there any restrictions or stipulations about mergers, mission, or end beneficiaries in existing constitutions? Would a merger impact the Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) or Public Benevolent Institution (PBI) statuses of either organisation?

- Stakeholders – Are there any key stakeholders who might be averse to major changes and could block or disrupt the merger? For example, organisation founders and their relatives, or retired board members.

- People and culture – Are there major differences in culture or enterprise bargaining agreements, if applicable, that might halt or inhibit the value that can be created by a merger?

5. Build the merger ‘business case’

A merger costs time, money, and resources and can be highly risky, so it is important to be clear on why the merger is better for end beneficiaries. We use the term ‘business case’ in quotes because while a non-profit merger is not about creating financial upside, a merger ‘business case’ in the social purpose sector should be similarly rigorous and include the following components:

- Strategic rationale and merger vision

- Improvements in outcomes for end beneficiaries

- Financial costs and benefits

- Financial scenario analysis

- Staff, stakeholder, legal, and tax considerations

- Opportunity cost – what could you do otherwise

- Risks and mitigation

- Implementation plan, including resource requirements and costs.

A key upfront question for the boards will be agreeing what topics they want covered in the business case and what level of detail do they require on each one? We call this the ‘burden of proof’. For low risk small acquisitions, the burden of proof may be low. Conversely, a full merger that will fundamentally change both organisations is higher risk and consequently boards may require more work and detail (i.e. a higher ‘burden of proof’) before they would consider approving the merger.

Clarifying why a merger is better for customers can and should require effort. It is not enough to say a merger is better because it will enable the organisations to reach more customers, offer more services, or simply do things better. To establish why a merger is better for customers, it is first important to understand what it is that end beneficiaries need and then what a merger can offer. After all, there is little point in reaching more people if services are currently subpar, offering more services if end beneficiaries do not want or need them, or ‘doing things better’ if it is unclear what should be ‘done better’.

… through that process, they identified the need to establish a new ‘Customer’ function…

To establish the case for why a merger would be better for customers, House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation defined their customer segments, developed customer journey maps to understand current experiences for each segment, identified key highlights and frustrations, and developed initiatives they could pursue to deliver improved outcomes for customers.

Notably, through that process, they identified the need to establish a new ‘Customer’ function responsible for regularly distilling customer insights, championing the voice of the customer within the organisation to help drive continuous improvement, and regularly monitoring and managing the health of customer journeys across the organisation.

Both organisations also identified initiatives that could deliver financial value and help fund the merger. Financial initiatives were bucketed into hard cost savings (e.g. real cash savings from planned technology investments), soft cost savings (e.g. savings from productivity that may improve efficiency but may not result in real cash savings), and potential revenue uplift.

Scenario analyses were run on the ‘business case’ to determine the best- and worst-case scenarios for the merger to ensure the organisations were equally prepared for both scenarios. The initiatives later served as the basis of merger planning and value capture after the merger was approved.

6. Plan and implement the merger

Once the merger ‘business case’ is established and approved, the next step is to conduct due diligence and design the merger if desired.

To approve the merger, both organisations must be sufficiently satisfied with the results of due diligence, where due diligence is the process of evaluating any elements that may be deemed to be ‘material’ to whether a merger should proceed. While the level of due diligence required depends on the risk appetite of each organisation, it is critical to ensure board members have satisfied their fiduciary duty to the organisation. Relevant topics to investigate during due diligence may include reviewing financial and operational data to confirm the merger ‘business case’ holds as described and reviewing any incidents and current or potential legal actions.

There are two options for merger design. The first option is to do detailed merger design and develop a detailed implementation plan. The second option is to leave detailed merger design until after transaction close, which would imply that both organisations would continue to operate unchanged for some time after day one of the merger. The choice depends on what each organisation needs to approve and effect a merger, and how much flexibility in timing there is for capturing value from key initiatives (e.g. are there anticipated savings from sharing a major technology investment that would be lost or dampened if the organisations wait too long and start investing on their own).

In either case, best practice suggests the following items be clarified at minimum to approve and effect a merger:

- Legal structure – What is the legal structure of the future merged entity? Typically, a merger will be structured as an acquisition, either by one organisation or by a separate parent entity, where the acquisition either entails a change of control or a transfer of assets. What changes, if any, need to be made to either organisation’s constitution?

- Member approval (for member-based organisations) – How will member approval be secured? Note that if the intent is to establish parent and subsidiary entities, all members of the subsidiary entity must resign and the new parent becomes the sole member of all subsidiary entities

- Board and leadership selection – How will the new board and board chair be selected? What key leadership roles if any need to be selected before merger approval and how will those roles be filled?

- Stakeholder engagement – What are the stakeholder engagement plans for customers, staff, funders, and government? Should any be engaged with before merger approval by the executive teams, boards, or the members?

- Operating model, value capture, and business integration – What does day one of the merged entity look like and are there any steps that need to be taken pre-day one? What values or elements of culture should be retained from each organisation and what will need to be actively shaped moving forward?

It is worth noting that for all these elements, there is as much a technical component as there is a strategic one. For instance, legal structure can be reduced to a technical exercise, however it is also worth considering how well a potential legal structure sets up the organisation to achieve its merger vision.

A skilled independent facilitator can be helpful to mediate discussions… on a new board and leadership acceptable to both organisations.

It is also worth touching on board and leadership selection briefly, as anecdotal evidence in the sector and through publications such as Pro Bono Australia and the Stanford Social Innovation Review suggests this is often an area where non-profit mergers fall apart.

Ideally, this should be touched on as part of the earlier discussions on non-negotiables and key principles so that there are no, or limited, surprises at this point. A skilled independent facilitator can be helpful to mediate discussions between parties and facilitate agreement on a new board and leadership acceptable to both organisations. It is also worth considering if and how people who are no longer in key board or leadership roles should be involved in the future organisation.

A merger is hard and we would caution any organisation against going lightly into a merger. However, we would equally encourage all organisations to regularly review and consider mergers (or other forms of collaboration) as a potential strategic option to maximise impact for end beneficiaries.

As Richardson says, “Our customers are at the centre of all we do. Put simply, we came together to help more people in more places. We’re passionate about upholding the rights of people with a disability. Together we will provide even better support and services to people with a disability, their families, and their carers.”

The proof of success will be in the clear evidence of better customer outcomes in the shorter term and improved financial sustainability in the medium term.

We are excited by the vision House with No Steps and The Tipping Foundation have developed and its potential for improved outcomes for people with disability. They are early on in their merger journey and it is premature to see results, however we look forward to seeing and sharing the story of their impact in years to come.

For Kelly, the proof of success will be in the clear evidence of better customer outcomes in the shorter term and improved financial sustainability in the medium term. “That was and remains the whole point of the merger,” he says.

Authors: Diana Ferner and Malcolm Garrow