We need to talk about class

Class and economic mobility are rarely talked about in Australian workplaces. Here Lisa Fowkes unearths insights that suggest that this should change, not just because family background shouldn’t dictate our fortunes, but because of the economic benefits of more inclusive practices.

- Declining economic mobility undermines social cohesion, threatening economic stability.

- While economic mobility in Australia has been strong relative to other countries, people born into poorer families will, on average, earn less than their peers.

- One of the factors that affects outcomes for people from less privileged backgrounds is the way employers use degrees to filter out candidates, even where a degree is not needed for the job. Segregation of cities and schools by socio-economic status also affects opportunity

- The first step to ensuring equitable access to employment is to make the issue of socio-economic diversity in the workplace visible.

- SVA is seeking to engage with employers and others with an interest in employer action on economic mobility.

In thinking about how we approach class and economic mobility in Australia, it is hard to ignore current headlines about tariffs and a potential US recession. We have entered a period of global economic instability triggered by the actions of the Trump Administration – an Administration that has successfully channelled the anger and pain of many American voters, particularly those without four-year college degrees. And it is no wonder they are angry. Since 2010, in one of the wealthiest countries on earth, the life expectancy of Americans without four-year degrees has declined.1 The gap in life expectancy between those with and without degrees was 2.5 years in 1992 and is now 8.5 years. The gap grew by more than three years during the pandemic. Wealth and income inequality alongside lack of economic mobility have polarised the American electorate, and are now threatening economic prosperity across the globe.

SVA is one of a number of organisations seeking to raise awareness of emerging risks to economic mobility in Australia, and the important role of employers ensuring a Fair Chance for young people from less privileged backgrounds. Read more.

Like the US, Australia has historically seen itself as a ‘classless’ society – a country in which success depends on hard work and motivation, not family background. Research conducted by Essential Media for SVA found that, amongst Australian employers, there is ‘no line of sight on class or economic inclusion’. It is not on their agenda. As a result, very few employers examine the socio-economic backgrounds of their workforces or check to see if their practices are locking in pre-existing privilege.

In the UK, by contrast, there is ongoing public discussion about the effects of class privilege on economic outcomes. Leading employers along with NFPs and the UK Social Mobility Commission regularly report how people from different economic backgrounds are faring at work. Reporting has revealed, for example, a 12% class pay gap for people in the same profession but from different socio-economic backgrounds – larger than the UK gender pay gap (7%). A report on the UK Civil Service workforce found that nearly three quarters came from privileged backgrounds – a profile that has barely moved since the 1960s.

As economic inequality increases in Australia, we can’t afford to ignore the ways in which this impacts on who ‘gets in’ and ‘gets on’ in Australian workplaces, or to disregard the role employers can play in ensuring people have a ‘fair chance’ to earn a decent income through work.

Is there a problem?

Australia is a more equal and more economically mobile country than either the United Kingdom or the United States. But recent analysis by the Productivity Commission shows that the future incomes of children born into families at either the top or bottom 10% of incomes are significantly impacted by what their parents earned. People who frequently experienced poverty as a child are more than three times as likely to experience adult poverty than those who never experienced childhood poverty.2 People who were never poor as children are more likely than others to be in permanent work, in full time work and to have higher hourly earnings than those who were regularly or often poor.

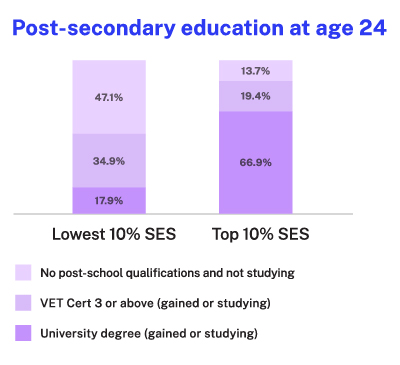

Researchers estimate that around 30% of inherited disadvantage is associated with educational attainment. The gap in educational attainment between young people from low and high socio-economic backgrounds is stark – with over 2/3 of those in the top 10% gaining a university degree by age 24 compared with only 17.9% in the bottom 10%.3 (See figure 1.) Young people from low income families are no less motivated to go to university, but identify financial barriers and family responsibilities as barriers to attendance.

4 Yet employers often look at university degrees as a proxy for other skills – like problem solving or communication – without considering how this might bias selection. In the US, where this issue has received more attention, researchers found that degree inflation (the practice of requiring university qualifications for jobs that do not require them) not only inhibits access to jobs for many capable candidates, but creates additional costs, for example in wages and reduced retention, without corresponding productivity gains.5

In recent years US employers, including federal and state governments, have started to drop degree requirements in favour of a greater focus on hiring for, and developing, the broader skills they need.6

Where you grow up also shapes economic outcomes. Those who spend their teenage years in a wealthier area tend to have higher incomes later in life, those in poorer areas to be poorer. One explanation may lie in the importance of social networks to employment outcomes. Many people find their first job, their first work experience opportunity or early career opportunities through family and social networks. Family and social networks continue to be the main way that young people find out about industries, occupations and careers. As schools and communities become more segregated by socio-economic status these informal mechanisms for offering opportunities are likely to exacerbate existing inequalities.

Socio-economic background critically shapes people’s employment experience. Diversity Council of Australia’s survey of over 3,000 workers found that self-identified class more than any of the other 8 diversity demographics surveyed (including gender, cultural background, disability status, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status), was the most strongly linked to workers’ sense of inclusion at work. Workers from higher class backgrounds were more likely to report being listened to by their managers, having trust in the organisation to treat them fairly, and to have access to opportunity. Workers from lower class backgrounds were more likely to report being ignored, being harassed or being left out of social gatherings.

Thinking about class background also sheds light on other diversity dimensions. Respondents to the DCA survey with disability, who were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders, non-Christian and LGBTIQ+ were more likely than others to identify as lower class. Lower class women were more likely to experience harassment. These findings suggest that employers wanting to understand the state of play in terms of inclusion and safety at work need to add a socio-economic background lens.

Moving forward

One of the problems in talking about economic mobility is that, by its nature, economic mobility research looks back in time. But there are signs that young people who entered the labour market following the GFC may be the first generation in living memory to be worse off than their parents. The Productivity Commission found that young people born in the 1990s have experienced a decline in wages relative to older workers, and have tended to move into lower skilled jobs, with lower earning potential.7 Increased school segregation and lack of affordable housing in job rich areas are likely to further divide rich and poor.

One of the first things that must be done in order to ensure that our workplaces do not further entrench inequality is to include socio-economic background amongst the measures that are collected to understand the make up of workplaces. Collection of data on gender equity hasn’t changed the world overnight, but it has enabled us to understand the types of practices that are locking in gender inequality, and allowed employers to consider how they might open up opportunities to different areas of talent. Not only should employers consider capturing data on the socio-economic backgrounds of their workers, governments should consider including socio-economic background in targets for its employment policies and for social procurement.

A second area for action is the development of new ways for young people from less privileged backgrounds to access career pathways. The NSW Digital Skills and Workplace Compact is an excellent example of this. Industry and government have recognised that current use of Information Technology degrees to select entry level candidates is locking out a wide range of diverse talent. Apart from anything else, this is simply not sustainable to meet industry needs. Signatories to the Compact have committed to recruiting 20% from ‘alternative pathways’ – that is, pathways that allow people to earn while they learn – by 2030. Provided these pathways are structured so as to create opportunities for people from low socio-economic backgrounds, this initiative could make a significant difference to thousands of young people who would otherwise be unable to work their way out of poverty.

Many areas of SVA’s work touch on these challenges. Through our Employer Innovation Labs we support individual employers to enhance economic mobility for young people through employment practice change within their organisations, and we are about to embark on more in depth work on ‘earn and learn’ pathways. With Australian Business and Community Network (ABCN), we are bringing together employers interested in leading the way in ensuring equitable opportunities for good quality employment for people from lower socio-economic backgrounds in their organisations, and are looking at ways to increase measurement of socio-economic background at work. As inequality deepens and AI starts to impact on pathways into work, it is time to act to make access to economic opportunity fairer.8

We are looking for others to work with us to support a ‘Fair Chance’ agenda for Australia, with a focus on rebuilding and enhancing economic mobility so that that all people, including those from low socio-economic backgrounds, can thrive.

1 A Case, A Deaton, ‘Without a college degree, life in America is staggeringly short’, New York Times, 3 Oct 2023, accessed 4 June 2025.

2 Dr E Vera-Toscano, Prof R Wilkins, Does poverty in childhood beget poverty in adulthood in Australia?, Breaking Down Barriers project, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, Oct 2020, accessed 4 June 2025.

3 S Lamb, Huo, A Walstab, A Wade, Q Maire, E Doecke, J Jackson, & Z Endekov, Educational opportunity in Australia 2020: Who succeeds and who misses out, Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University for the Mitchell Institute: Melbourne, 2020, accessed 30 May 2025.

4 S Lamb, Huo, A Walstab, A Wade, Q Maire, E Doecke, J Jackson, & Z Endekov, Educational opportunity in Australia 2020: Who succeeds and who misses out, Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University for the Mitchell Institute: Melbourne, 2020, accessed 30 May 2025.

5 J Fuller, M Raman et al., Dismissed by degrees, published by Accenture, Grads of Life, Harvard Business School, Oct 2017, accessed 30 May 2025.

6 JB Fuller, C Langer, J Nitschke, L O’Kane M Sigelman & B Taska, The emerging degree reset: How the shift to skills-based hiring holds the keys to growing the US workforce at a time of talent shortage, The Burning Glass Institute. 2022, accessed 30 May 2025.

7 The Productivity Commission, Fairly equal? Economic mobility in Australia research paper, 2024, p35

8 A Raman, ‘I’m a LinkedIn Executive. I see the bottom rung of the career ladder breaking’, The New York Times, May 2025, accessed 4 June 2025.

Get in touch

Find out more about SVA’s work in raising awareness of risks in economic mobility and ensuring a Fair Chance for young people from less privileged backgrounds.

-

Director, Employment Lisa Fowkes

Director, Employment Lisa Fowkes