Purpose-driven measurement: Why the ‘why’ matters in grant making

Funders, whether government departments or philanthropists, are united by a single ambition: to create significant, lasting impact. Yet, the path to understanding that impact is often cluttered with complex metrics and burdensome reporting requirements. We frequently see funders requesting extensive data from grantees without a clear strategy for how that data will be used. This lack of intentionality can impose a significant burden on the very organisations the funder seeks to support, diverting precious resources away from service delivery.

To move from merely collecting data to truly understanding impact, funders must first ask themselves a fundamental question: what will we use the results for?

The answer—the ‘why’—dictates the ‘how’. Understanding your purpose is critical because different aims often require contradictory measurement approaches. Here are the five most common reasons for measuring outcomes and what they mean for your funding strategy.

1. Tracking performance (accountability)

This is the most common starting point: is the grantee doing what they said they would? For example, a program designed to reduce school refusal might track attendance rates.

The implication: If the goal is simply a ‘check and balance’ to confirm progress, avoid over-engineering the solution. Extensive quantitative reporting can be resource intensive. Consider a lighter touch, measuring only 2-3 highly relevant outcomes, or use a ‘one-page vignette’ or narrative reports that verify activity without drowning the grantee in paperwork. This approach pairs well with flexible funding, allowing organisations to pivot as circumstances change while remaining accountable to the agreed impact.

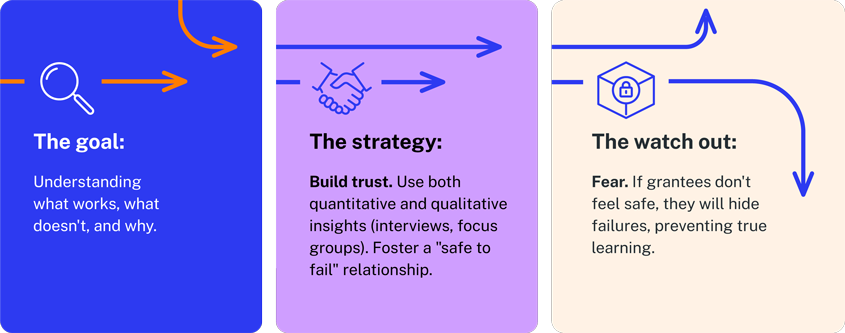

2. Learning and improving (innovation)

Outcomes data can be a powerful tool for collaboration, helping funders understand what works and what doesn’t. This is essential for supporting innovative ideas and complex social interventions.

The implication: Learning requires trust, not just data. Quantitative measures tell everyone what happened, but rarely why. To truly learn, take a growth mindset and build a relationship where grantees feel safe admitting failures. Measurement here should likely be bespoke (led by the organisation or co-designed) and accompanied by qualitative insights—interviews or focus groups—to capture the nuance of success and failure.

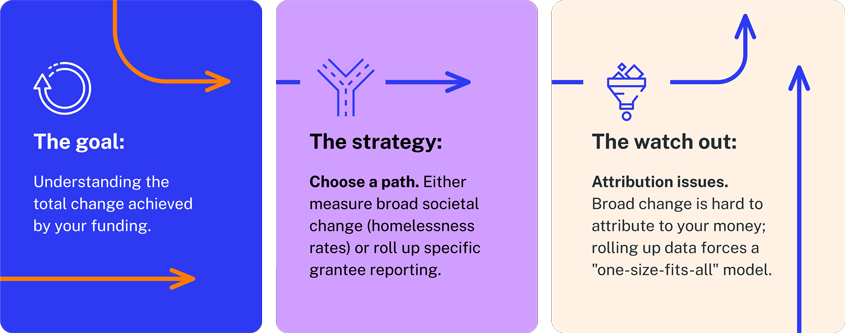

3. Demonstrating total impact (the portfolio view)

Many grant makers wish to aggregate their impact to understand the total change their funding has achieved.

The implication: Measuring ‘total impact’ is notoriously complex. You cannot simply sum up disparate programs or see an alternate history of what would have happened without the funding. There are generally two paths:

- Measuring overall change: Measuring broad changes (e.g. homelessness rates in a specific city) gives a holistic picture of impact but makes it hard to attribute success to your specific funding.

- Rolling up reporting: Asking all grantees to measure the same outcomes allows you to combine results. However, this forces different programs into a ‘one-size-fits-all’ framework, which potentially doesn’t capture the actual change organisations are creating.

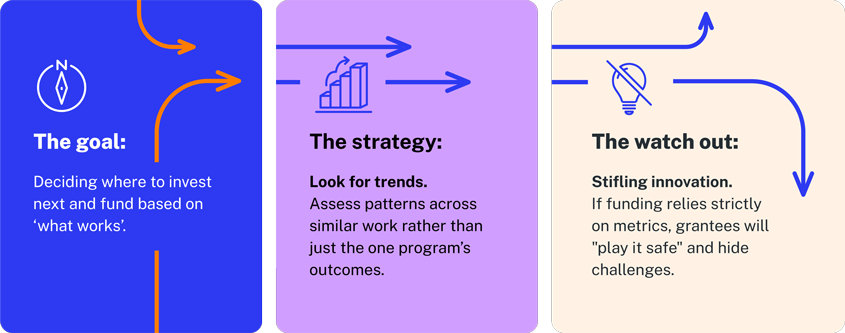

4. Informing future funding (strategic allocation)

Funders naturally want to back winners. Investing in programs that have previously created good outcomes seems logical.

The implication: Proceed with caution: it’s vital to differentiate between withdrawing support for a failed program and cutting off an organisation simply because it ran a failed program. If grantees believe that organisational funding relies on always running successful programs, it acts as a brake on innovation – trying something new always carries a risk of failure. Grantees may also feel pressure to only report good news, hiding challenges. In addition, a program’s success is often context-dependent – it might have worked because of a particularly good program manager, or hard-to-replicate circumstances. Rather than relying on a single data point, look for trends across similar work to guide your strategy.

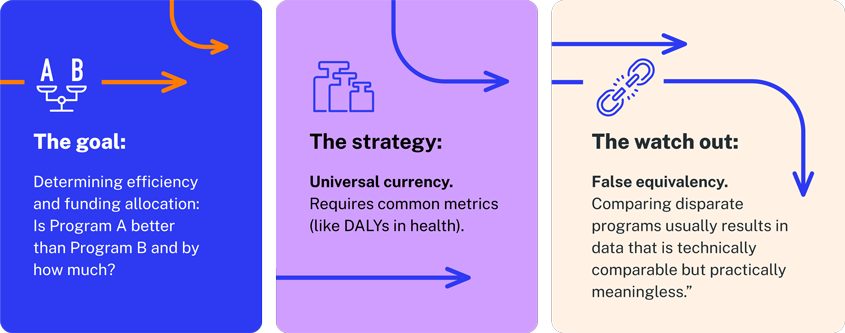

5. Comparing programs/organisations (benchmarking)

The desire to maximise impact often leads to the desire to compare: is Program A more effective than Program B? Should we only fund one or the other? How much should each get in funding?

The implication: Systematically comparing different programs is costly and difficult. It requires a common measure, a ‘universal currency’ of impact. In specific sectors like health, proxies like Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) exist. In others, they do not. Attempting to force disparate programs into a comparative framework often results in data that is technically comparable but practically meaningless. There are other ways of benchmarking success such as looking at similar programs or organisations across Australia, but the same caveats apply.

The strategic trade-off

There is an inevitable tension in impact measurement: the tension between bespoke and standardised.

- Bespoke measurement accurately reflects the unique work of a specific grant, making it excellent for tracking performance and deep learning. However, it makes comparison across your portfolio nearly impossible.

- Standardised measurement allows for comparison and aggregated reporting but often fails to capture the actual impact and nuance of individual programs, reducing the value of the data and potentially alienating grantees.

Conclusion

Outcomes measurement can be a powerful tool for impact but does have costs and side-effects. As a funder, your role is to be intentional. Do not ask for data you do not intend to use or cannot be useful.

If you want to learn, favour bespoke measurements and qualitative insights, and build trust. If you want to compare, acknowledge the cost of standardisation and the potential loss of understanding the actual change achieved. By clarifying your ‘why’ before you request the ‘what’, you protect resources and ensure your funding delivers the impact you seek.