How ‘help seekers’ are informing Lifeline’s digital service innovation

This story from the field demonstrates how Lifeline Australia brought the beneficiary voice and experience into developing a text-based, crisis support service.

- Lifeline offers perhaps the most well-known and trusted helpline in Australia’s crisis support and suicide prevention system.

- With support from SVA and Today Strategic Design, Lifeline Australia has piloted a text-based, crisis support service known as Lifeline Text.

- Lifeline’s primary motivations for developing the service are to increase reach, improve outcomes for service users (known as help seekers) and boost efficiency.

- On its journey towards a text-based, crisis support service, Lifeline has learned some critical lessons about the importance of deeply understanding service users to unlock the full possibilities offered by digital technology.

Lifeline is one of the more important and ubiquitous services in Australia’s crisis support and suicide prevention system. Last year alone almost one million Australians used Lifeline’s services when they found themselves in crisis, considering suicide or struggling with mental health challenges.

This article is a story from the front line of crisis support. It shares how Lifeline is adapting to changes in behaviour and advances in technology to better meet the persistent issue of suicide in Australia. It explores Lifeline’s journey towards digital transformation and in particular, the development and testing of a text-based, crisis support service.

It will outline how Lifeline Australia has taken three important steps in this journey:

- building a team for change

- listening to and learning from help seekers and crisis supporters

- planning for and building a new service and business model.

About Lifeline

Lifeline Australia is a national charity that works in partnership with a network of accredited members across the country to deliver a range of crisis support and suicide prevention services. These include the flagship 24-hour national helpline (13 11 14) and an online chat service. Lifeline has over 11,000 dedicated volunteers of which around 3,500 work as telephone crisis supporters. The organisation enjoys around 97% brand recognition, is well trusted by the Australian community and is ever-present in the media and public sphere.

… more than 3,100 people in Australia died by suicide, that’s almost eight lives lost per day.

The need for Lifeline’s services is undeniable. In 2017 alone, more than 3,100 people in Australia died by suicide, that’s almost eight lives lost per day.1 In many demographics, suicide rates are on the rise, causing some to suggest that Australia is facing a national suicide emergency.

However, despite high prevalence rates, rates of help seeking in Australia remain low2 and Lifeline does not currently support important demographic groups as much as it would like (e.g. young people, rural communities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning or intersex [LGBTQI]) who are over represented in suicide statistics but under-served by Lifeline.

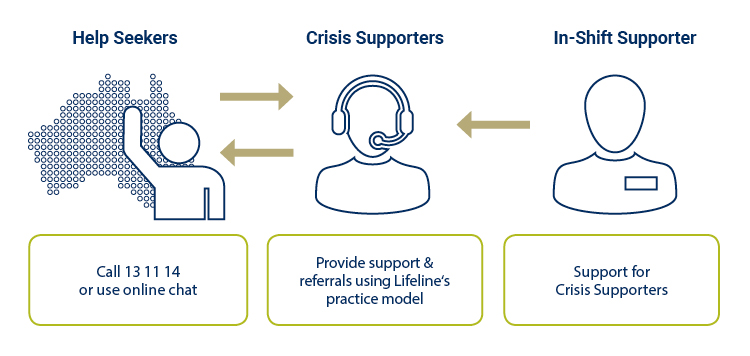

Key terms used in the Lifeline service model

Help seeker: A person looking for assistance from Lifeline. (Other organisations may refer to their ‘client’, ‘beneficiary’ or ‘service user’.)

Crisis supporter: An individual who has undergone Lifeline’s crisis supporter Workplace Training (CSWT) and holds conversations with help seekers. These are mostly volunteers at Lifeline.

In-shift supporter: The individual providing in-shift support to crisis supporters during a shift. The in-shift supporter may be required to decide on contacting police in the event of an imminent safety issue or if a crime or emergency is identified during the conversation. These are mostly paid staff at Lifeline.

“Since launching in 1963, Lifeline has a proud history of service innovation and introducing new channels to support help seekers,” said Colin Seery, CEO at Lifeline Australia.

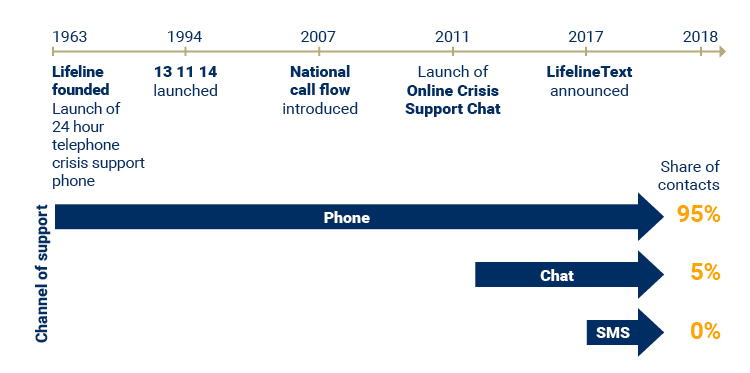

Several past innovations include the consolidation of all calls through a central line in 2007 to improve service quality and efficiency (National call flow) and the launch of an online chat service in 2011.

“Our current strategy highlights the importance of using technology better to reach more help seekers and we are keen to push that forward,” said Seery.

Figure 2. Lifeline’s history of service innovation

Meanwhile, Australia has witnessed two major social and technological trends over the past 20 years. The first is an explosion of new communications channels (including text, smart phones, social media and messaging apps) and our changing preferences for using these tools in a range of professional and personal ways. The second is the rise of algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI) and chatbot3 technologies. For example, one survey suggests that 58% of people will search the web to avoid making a medical appointment.4

Building a team for change

In 2016, Lifeline Australia’s Leadership Team secured a $2.5m Commonwealth grant to pilot a text-based, crisis support service. The project was called ‘Lifeline Text’.

“Our rationale for developing Lifeline Text was straightforward but compelling,” said Alan Woodward, then Executive Director Lifeline Research Foundation.

“We saw three main reasons. First, text is one of the most commonly used modes of communication today. Second, charities like Lifeline in the UK and USA are already offering crisis text services and the response from international help seekers suggests popular adoption and positive impacts for suicide prevention in Australia. Finally, Lifeline Text has the potential to reach more people and a wider demographic seeking help at a time of crisis, some of whom may not use the telephone or online chat.”

Today was brought in to help us engage more deeply with help seekers and our workforce and start to bring the service to life.

In February 2017, Lifeline Australia engaged SVA Consulting (SVA) and Today Strategic Design (Today) to support them in the development of Lifeline Text. SVA was focused on the strategic fit, service design and business model for Lifeline Text. SVA also supported overall project management during the early stages of the project and helped ensure that Lifeline had clear and robust implementation plans. Today, specialists in human-centered design and technology, worked with Lifeline to conduct research with help seekers and crisis supporters to ensure the new service was informed by the specific needs of end beneficiaries and frontline workers.

“SVA helped us establish the service design process, identify desired outcomes for the overarching project and do some of the required financial analyses to better understand what might be feasible,” said Dr Sally Bradford, Senior Project Manager. “As a strategic design company, Today was brought in to help us engage more deeply with help seekers and our workforce and start to bring the service to life. It was a good balance of skill sets for what we wanted to achieve with Lifeline Text.”

As part of this team, Lifeline provided critical knowledge of the practice model and how it might be adapted for text as well a deep understanding of the complexities of delivering a service across the Lifeline network.

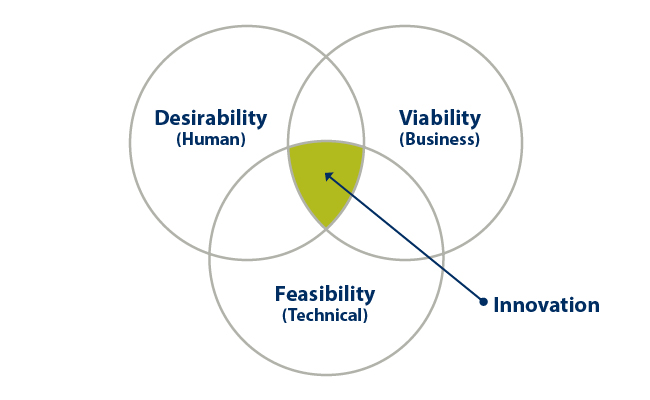

Throughout the Lifeline Text project, Lifeline Australia had three factors top of mind:

- Desirability: What do people want? Lifeline wanted to ensure the voice and needs of both help seekers and crisis supporters was at the centre of the new service

- Feasibility: What is technically and operationally possible? Lifeline wanted to know what technology could deliver Lifeline Text, but also how it might be delivered as a national service across Lifeline’s membership network

- Viability: What is financially sustainable? Lifeline needed to understand potential service demand to estimate the cost of the service from day one to the end of the two-year pilot.

Initial research and engagement with external experts and practitioners in the crisis support field ensured best practice was at the forefront of the team’s thinking. International services such as Crisis Text Line in the US and the UK Samaritans’ SMS-based service provided strategic and operational insights, including how quickly the demand for a similar service might grow in Australia, and how AI and chatbots could be integrated into a service that relies on human empathy and understanding.

Listening to and learning from help seekers and crisis supporters

What might a help seeker think, feel and do if they contacted Lifeline via text? Does a text conversation remove the ‘human connection’ that help seekers value in a phone conversation? How would Lifeline’s crisis supporters adjust to this different channel, without the rich cues of voice and ambient sound? What are the broader implications of SMS technology for Lifeline’s practice support model and services? These were just some of the questions investigated across two distinct but complementary phases of participatory and human-centred design research.

What is human-centred design?

Human-centred design (HCD) is a process and set of tools used for problem solving, increasingly used in the social sector. HCD “starts with the people you’re designing for and ends with new solutions that are tailor made to suit their needs.”6 It reflects a commitment to designing a product or service based on a deep understanding of the context, needs and expectations of people.

Phase one: understanding service users

In the first phase, a series of workshops, interviews, and co-design sessions led by the team at Today provided an in-depth understanding of potential help seeker and crisis supporter needs and requirements. The 25 participants included current Lifeline workers and those with lived-experience of crisis support.

Both help seekers and crisis supporters provided several ideas and opportunities, from ways to improve the design of the conversation, to conversation wording…

What the team heard and saw during the HCD process validated existing research into technology and mental health: that a text-based technology has positive benefits for help seekers in crisis, and that the loss of human cues does not diminish a conversation’s effectiveness.

Both help seekers and crisis supporters provided several ideas and opportunities, from ways to improve the design of the conversation, to conversation wording, and what more Lifeline could do after a conversation is completed. Help seekers and crisis supporters didn’t just validate or invalidate the team’s assumptions, they also actively participated in designing how the service might be delivered.

Several key insights from help seekers emerged:

- They are looking for a non-judgemental and objective human connection in the first text message

- They don’t mind the use of chatbots in a text conversation, as long as it’s clear when they are getting automated messages and when it’s a human

- They want text to be used to give them choice and agency.

I don’t want a cut and paste job. I want it to be just for me. – Help seeker

The crisis supporters also provided important insights:

- Phone crisis supporters hold vastly different assumptions and expectations of a text service than webchat crisis supporters

- Crisis supporters desire much more information and training before they will feel confident delivering a text-based service

- Crisis supporters expect a text-based service to provide data from their activity to improve their personal performance.

It (text) is taking us out of our comfort zone. It’s a different way of thinking. – Crisis supporter (phone)

Phase two: working service prototype

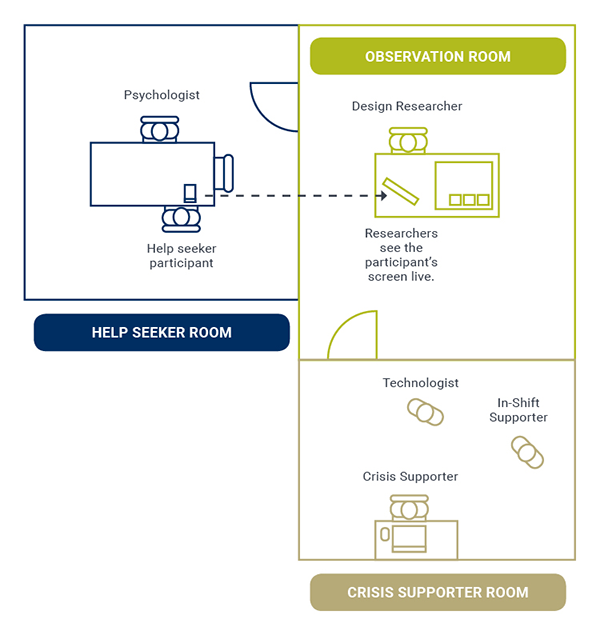

The second phase of research was a collaborative effort between Today and Lifeline Australia. In this phase, the fidelity of research to the real-world service was increased – moving from paper prototypes to a working service prototype, complete with mobile phones for help seekers and chat software for crisis supporters. Given the sensitive nature of the research, Dr Bradford sought ethics approval through the Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC),7 and both a Lifeline In-Shift Supporter (ISS) and Dr Bradford, a clinical psychologist, were on-site for every simulation to ensure participant well-being.

… we were able to co-design the service with the people who actually use it…

With input from an expert advisory group, the project team ran innovative simulations of the help seeker/crisis support interaction. Each of the 14 simulated sessions had one participant (as the ‘help seeker’) and one trained Lifeline crisis supporter, separated in different rooms. After the conversation, the design researcher, Dr. Bradford and the ‘help seeker’ went over the conversation together to identify ways to improve the service.

“Not only were we able to simulate aspects of the service to a fine detail, but we were able to co-design the service with the people who actually use it,” said Tait Ischia, the then Service Design Lead at Today. “This was the first time Lifeline had been able to conduct a conversation with a help seeker and ask them to actively input into improving the service immediately after.”

It has provided new depth to our understanding about what people expect and need when they are in crisis…

This second phase uncovered details about staffing and training requirements, ways to improve the conversation experience and the technology, and ideas to tweak the practice model for text.

“Our research with Today and SVA enabled us to design the service with help seekers and crisis supporters. It has provided new depth to our understanding about what people expect and need when they are in crisis,” said Dr Bradford. “We also have a better appreciation of the technology challenges, new ideas for evolving the service model and specific directions for how our workforce will need to be trained.”

Planning and building a new service and business model

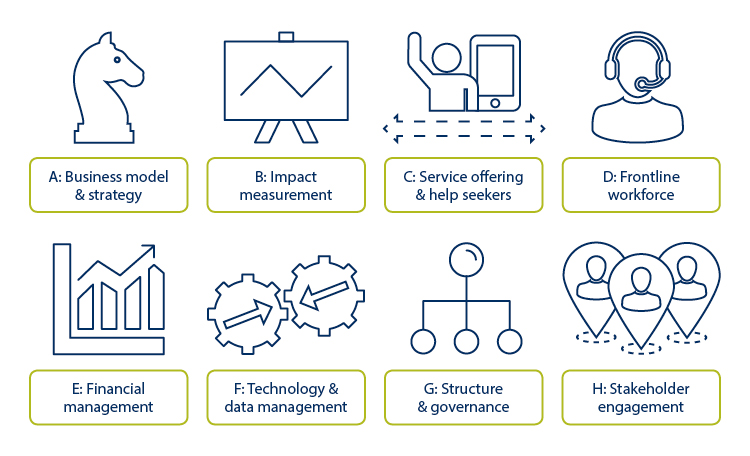

In parallel to the human-centered research, the Project Team established eight separate but overlapping ‘work streams’ to do detailed service and operational design and implementation planning.

The team considered a range of possible business and operating models to deliver Lifeline Text and agreed on a set of criteria for how these decisions would be made. Impact measurement was an essential work stream and Lifeline’s existing program logic was adapted for text and an evaluation approach developed. In addition to the human-centered design research, Lifeline also needed to estimate the likely demand for the service and the corresponding workforce that might be required if the service was to be delivered in the future. The team forecast that the service could grow very quickly to be a full scaled service within two to three years of operation.

… the independent evaluation… has shown that our service model resulted in significant improvements for help seekers across all outcome measures…

“We were well prepared for the pilot that was launched in July 2018,” said Dr Bradford. “And the independent evaluation of the trial by the Australian Health Services Research Institute (AHSRI) at the University of Wollongong has shown that our service model resulted in significant improvements for help seekers across all outcome measures, and that the service is financially viable and cost-effective. We now have a good sense of what is required to deliver an ongoing national, text-based service.”

Outcomes and future directions for Lifeline

Over the last two years of development, Lifeline has matured in three main areas:

1. Greater focus on service users.

Lifeline has built stronger internal skills for designing and delivering human-centred services. Lifeline has also now launched a lived-experience advisory group to help inform future services.

2. Improved project management capability

Over the course of the project, Lifeline has formally established a Project Management Office (PMO) and has developed capability in project design and delivery across different parts of the organisation. The implementation plans that were developed across all eight work streams have been helpful guiding documents for the team in the lead up to the Lifeline Text pilot.

3. Increased momentum towards a digital transformation

The Lifeline Text project has shown the organisation the power of technology to improve organisational effectiveness and efficiency. It has had a ripple effect for Lifeline to consider how digital technology could be further integrated within its strategy. This could include not just offering text as an additional channel, but also providing a suite of integrated multi-channel services that reach a greater diversity of help seekers and prioritise support. It could also include building adaptability to harness AI and emerging digital technologies.

“We’ve started engaging with our members and Board to better define the key elements of this next step in our own digital transformation,” said Seery, CEO at Lifeline Australia.

“We believe these types of services are increasingly necessary in Australia. With the Lifeline Text service now underway, there are some exciting new directions for how the whole Lifeline network can better support help seekers in this country. We just need the right level of investment to make this a reality.”

See the Lifeline Text

For 24/7 crisis support or suicide prevention services, please call 13 11 14. If life is in danger, call 000.

1 Australia Bureau of Statistics, Intentional self-harm, key characteristics

2 Australian Bureau of Statistics, National survey of mental health and wellbeing: summary of results.4326.0 Canberra 2007

3 A chatbot can be defined as ‘a computer program designed to simulate conversation with human users, especially over the Internet’.

4 NPS Medicinewise/Galaxy Research, Media Release: ‘Dr Google’ is here to stay, 25 August 2016

5 IDEO Human Centered Design Toolkit

6 ibid

7 Under the title Lifeline Text: User testing and co-design of a new crisis text service (approval No: 09-2017)

9 Research design and diagram developed by Jo Szczepanska, Head of Co-design at Today.

Author: Jon Myer

Contributor: Susie King