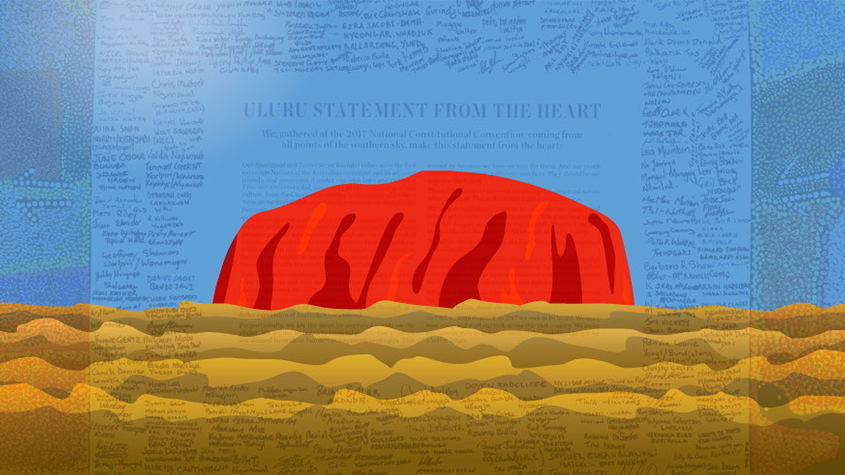

The Uluru Statement from the Heart: what now?

Professor Megan Davis, the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law and Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous at the University of NSW, and primary architect of the regional dialogues behind the Uluru Statement from the Heart, talks to SVA’s CEO Suzie Riddell about the Statement, where it is up to and why it is so important.

- The Uluru Statement from the Heart is an invitation from First Nations people to all Australians: “To walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.” It calls for a First Nations Voice to Parliament enshrined in the Australian Constitution.

- Professor Megan Davis provides an update about what has happened since the Statement was issued as well as how the Statement is different to what has been tried in the past. She emphasises that there hasn’t been any redistribution of public power in a way that empowers Aboriginal people.

- Professor Davis also shares the ways that organisations and individuals can contribute to the vision of a reconciled Australia.

View the conversation on video:

The Uluru Statement from the Heart calls for a First Nations Voice to Parliament enshrined in the Australian Constitution. This would be a permanent institution for expressing First Nations’ views to the parliament and government on important issues affecting First Nations people. The Statement also seeks a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making with Australian governments and oversee a process of truth-telling about Australia’s history and colonisation. Makarrata is a Yolgnu word meaning ‘a coming together after a struggle’. These reforms are summarised in three words: Voice, Treaty, Truth. Issued in May 2017, the Uluru Statement from the Heart is an invitation from First Nations people to all Australians: “To walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.”

Suzie: You’ve been deeply involved in the development of the Uluru Statement from the Heart and were among the 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates at the First Nations National Constitutional Convention back in 2017 – the people who were brought together to reach a consensus on the most meaningful and appropriate way to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the constitution.

Megan: It’s three years post the Uluru Statement being issued to the Australian people and it’s a complex framework of reform commencing with the constitutionally enshrined voice to Parliament.

We currently have a process led by the Minister [for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt] to design what a voice might look like. They intend to have a consultation period over December, January and February with the Australian community reporting back to cabinet. Not the most ideal time.

After this the Prime Minister has said he will look to the legal form of the voice.

The voice to Parliament will always be in legislation. What we’re asking for is for there to be a clause inserted into the Australian Constitution that establishes the power to set up a voice to Parliament. We think that’s important for many reasons, one being that if the government was to legislate for this voice before there’s a referendum, then there will be no referendum on a voice to Parliament. That will be disappointing to all those people that participated in the process over the past five years because they were asked the question by government: what is meaningful recognition to you? And the answer was a constitutionally enshrined voice to Parliament.

Professor Megan Davis is the Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous and Professor of Law at the University of NSW (UNSW). She is also currently the Acting Commissioner of the NSW Land and Environment Court, Balnaves Chair of Constitutional Law, a Member of the United Nations’ Human Rights Council’s Expert Mechanism on the rights of Indigenous peoples, and a Commissioner on the Australian Rugby League Commission, among many other roles. Professor Davis leads education and law reform work from the Indigenous Law Centre, UNSW Law with the cultural leadership from Uluru to deliver the mandate of the Uluru Statement via www.ulurustatement.org

Suzie: Where are we at now? And as a constitutional law expert what do you hope that the statement is going to achieve from here?

“We are going to embark on that process which opens up the design to non-Indigenous Australians…”

Megan: They wanted the security of enshrinement in the Australian Constitution so that it creates durability and sustainability and certainty for our people so that we’re not subject to the whim of the department, or the agency [National Indigenous Australians Agency] as it’s called. But rather Aboriginal affairs is elevated out of the realm of politics and party ideology, so that that voice endures for all time and not just from one party to the next. The greatest fear and risk of a solely legislated voice is that, as has happened in the past, it will be repealed from one government to the next.

We are going to embark on that process which opens up the design to non-Indigenous Australians which will create an interesting dynamic.

“Under that umbrella we’ve been pushing forward in what we now call the Uluru Dialogue – the dialogue between the Australian people and First Nations peoples.”

In the meantime, for the past three years, me and Aunty Pat Anderson and others have been maintaining the Uluru leadership – a large group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders and a very large group of non-Indigenous supporters and Uluru Youth, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, who have been meeting regularly, for the past three years on pushing the reform forward by working together to educate Australians. We do this supported by the Indigenous Law Centre at the University of NSW (ILC) whose primary work is community legal education.

One of the first things the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership did after Uluru was to set up our own website presence called ulurustatement.org. This was immediately after and before anyone had heard of the statement. Under that umbrella we’ve been pushing forward in what we now call the Uluru Dialogue – the dialogue between the Australian people and First Nations peoples.

We’ve been doing a lot of work around the country – we have our dialogue groups in every single state and territory. They are the people who participated in the Uluru dialogues and the constitutional process set up by the Referendum Council that I was a part of. So the same leaders and many more have continued doing this work on the ground in grassroots communities for three years, trying to build that network of Australians. We also have large numbers of people who weren’t at Uluru. We are very inclusive as it is a movement for all Australians.

Recently we have launched a special project with SBS where we have had the Uluru Statement translated into 62 languages. Australians can go on to the ulurustatement.org website and read these translations, and on to the SBS website to hear the translations.

We’ve partnered with Midnight Oil who have put out a marvellous mini-album on Makarrata with a song about the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Aunty Pat Anderson and Stan Grant and Adam Goodes, all supporters of Uluru are recorded. And there are many other partnerships and projects that we are doing around educating the Australian people on this voice to Parliament.

That’s where we are at the moment.

Morrison really wants to know that the Australian people will support this. A big part of the work of all of the Australians involved with the Uluru Dialogue out of the ILC UNSW is to keep working, keep getting together weekly, and keep educating Australians on the importance of change.

Suzie: Many people have seen decades worth of endeavours to create real and lasting change. What are the defining features that mean that this is different to what’s been tried in the past?

Megan: There’s a couple of them and it’s a good question. One thing I would say is that Australia has never effectively engaged with or implemented the right to self-determination. We haven’t seen the kind of change that self-determination can elicit yet for a few reasons.

If you look at the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report, it took two approaches. The first approach was if blackfellas come into contact with the criminal justice system these are some of the things that we can do to protect them, and in particular protect their lives – especially around the failure of the police and other custodial institutions to issue proper duty of care when it comes to protecting those people in custody.

But the Royal Commission did a second piece of work; it looked at why this is happening. It said: “The only way to protect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their lives in this country is to stop them from coming into contact whatsoever with the criminal justice system.”

There’s a very direct recommendation around the right to self-determination in the Royal Commission. They said the most important thing that needs to happen in Australia is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people need to be left alone to create autonomous arrangements that allow them to take control of the wheel.

“What we haven’t tried is providing any kind of structural power to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

And then it expressly says that bureaucrats have to exit the stage – that bureaucrats have to leave communities and leave communities alone and stop trying to control our lives. But in 2020 we’re looking at a situation where bureaucrats are never more in control. In fact, sometimes some of the language around this new voice design sounds like it is about entrenching bureaucrats in their role in our space.

We haven’t tried the right to self-determination. There’s a threshold of institutional arrangements that allow governments and countries to implement self-determination properly. And that is structural power. That is at the core of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

What we haven’t tried is providing any kind of structural power to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

When they talk about constitutional recognition they would be OK with symbolism, or a statement of recognition – something that recognises that we exist. But that’s not what our people want.

What we haven’t seen in Australia is any redistribution of public power in a way that empowers Aboriginal people. And part of that is, as I said before, removing the Aboriginal issue from the realm of politics and party ideology. That’s part of the thinking behind the enshrined voice in the parliament, because we haven’t tried constitutional reform – not substantive constitutional reform.

1967 was the deletion of an exclusion. We have never included our people. So even all of the arguments for a treaty; a treaty at a state and territory level is not going to garner you the power that is required to change the situation in Australia.

“We want to use the force of law in the highest document to compel the state to have us at the table…”

You need to compel the government to have you at the table – they don’t do these things because they’re nice people. You must force them to have you at the table and that’s what we’re asking for. We’re saying that when coronavirus happens, we want a seat at the table. When bushfires happen, we want our people, our Traditional Owners at the table. Anything to do with superannuation, we want our people at the table.

We want to use the force of law in the highest document to compel the state to have us at the table because we know governments come and governments go and some governments, they’re OK with Aboriginal people and Aboriginal rights, and then other governments are hostile to Aboriginal people and Aboriginal rights.

To change this and to move forward we have to engage the Australian people in the same way that we did in 1967. This must be the people dragging the politicians to the table because the system is ours – it is all Australians, and it is Australians who change the constitution. It is Aussies who change the constitution not politicians. We feel reasonably confident that Australians will support this and walk with us, and that’s why we did what we did.

Suzie: In terms of contributing to the vision of a reconciled Australia, what is working and what role would you like to see from organisations like SVA and philanthropists in the future?

Megan: It’s a good question because I’ve always been, as an academic, hypercritical of the process of reconciliation. Because in Australia it has been quite ritualistic and not one that really requires people to engage with the fundamentals of truth and justice. I think Australia’s reconciliation process has famously jumped over the truth and justice element of what reconciliation processes are.

The truth part will be when the nation is able to articulate some of the fundamental grievances that are held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about the dispossession and what has come since.

“We deliberately designed it in a way that the people in the room were the people who don’t have a voice…”

The justice part is around the question of repair – governments go to Aboriginal peoples across the world and they say, “Look, this is what’s happened because we had a truth process. What does repair look like to you?” And that’s a big part of what the Uluru dialogues were. We asked people – grassroots, low-income people; not the black elites or any of the black leaders that get to talk to politicians or go to Canberra.

We deliberately designed it in a way that the people in the room were the people who don’t have a voice, who don’t get to say what they think regularly and routinely. And what they said was repair, an enshrined voice, an entrenched voice, a voice of First Nations peoples, our Traditional Owners, back in communities – not in the cities and not in Canberra – but communities on the ground being able to say what they think and feel about laws and policies. That’s really critical, it’s really fundamental work.

With my United Nations hat on when I think about the work that we do in development and around capabilities, it’s a really fundamental principle of having those communities on the ground involved in this work. Uluru in some ways is retrofitting the truth and justice element that reconciliation hasn’t yet brought to the table.

Now having said that, when Uluru was handed down and when we started talking about an enshrined voice, the groups that understood the voice immediately were the RAP community – people who have reconciliation action plans – because they had built into their structures a consultation process that required them to speak to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples when they were doing things within their business or their not-for-profit or university.

I think about Andrew Mackenzie, the former CEO of BHP, who took a whole year of consulting his Traditional Owner (TO) groups before BHP endorsed the Uluru Statement. They had a mechanism set up and the TOs were all universal about their support for Uluru and they did a marvellous endorsement of Uluru in Perth where he invited and flew over TOs from all over the country.

RAP organisations really understand this notion of a voice.

“… we want you to just be quiet and reflect upon what people are trying to say here and support the Uluru Statement.”

What organisations like SVA and their networks can do to contribute to the vision of a reconciled Australia is to reflect carefully on the Uluru Statement and the reforms embedded in them.

Too often we see people coming back and saying, “Oh well, really we should do truth first, and really you should try this first, and really you should try that first.”

We’re trying to say to people, we want you to just be quiet and reflect upon what people are trying to say here and support the Uluru Statement. That is what we need. We need Australians to support an enshrined voice to Parliament in the constitution. We need philanthropists and organisations to help us provide the government with the confidence that the Australian people will support this.

That’s important, because it’s that very key element of truth and justice.

“The Uluru Statement is a sign of peace. It’s an engagement in a peace process with the Australian people.”

What does repair look like? Well we spent two years putting this together – this is a framework of repair that is not dissimilar to the ones that have come before through the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and the Barunga Statement and Yirrkala Bark Petitions.

We want people to support it as a very robust framework. Not to second guess us, not to tell us that we got it wrong, not to try and switch around the sequence so truth comes first and treaty comes last, but to really think that after so long – so long after the dispossession, so long after racial segregation, so long after assimilation, we’ve put together a really clever roadmap forward. Elites and politicians have tried to say truth-telling must come first, but such interventions only serve to validate the experience of people on the ground that those with a voice who purport to represent them decide what is better for them and strip them of agency. Rearranging the sequence of the reform only serves the status quo.

The Uluru Statement is a sign of peace. It’s an engagement in a peace process with the Australian people.

“… we need the Australian people to help convince the politicians that this isn’t just another trivial Pollyanna issue…”

There is this silence in the nation about that original dispossession and we all carry that – our country carries that, our people carry that, the Australian people carry that. And unless we resolve that, I look at all the very fine projects that SVA is engaged with, a lot of it becomes lipstick on a pig if we won’t talk about the really fundamental problem here. So it’s serious business – it’s as serious as anything this nation has ever faced.

But we are quite capable of fixing this – it’s just we need the Australian people to help convince the politicians that this isn’t just another trivial Pollyanna issue that you just put to one side for another electoral cycle. There’s urgency here and it’s partly because our old people are dying, our languages are dying with them, and they really want some peace for the country.

They want peace for the land, the country that they look after. They were very adamant about that and they were really the bridge builders in all of the dialogues. You had a lot of very young, angry people but you had an incredibly generous, older generation saying, “The Australian people will get this. We must engage them – we must be generous in our words and our actions towards them and we must ask them to come on board.”

Suzie: If there was just one thing that you haven’t shared yet that you’d like for our audience to hear or to do, what would it be?

Megan: There’s a couple of things.

Signing up to the Uluru Dialogue on the ulurustatement.org website would be great.

“There’s a process that will start in December that requires Australians to engage with the model of a voice to Parliament, and we’re going to ask people to make a submission.”

A lot of the information and the work we do is driven from the dialogues. So we’ve maintained the dialogue structure and it has all the key leaders still participating, plus all the other mob that came on board.

We still see it as deeply connected to our cultural authority. So when you sign up to the ulurustatement.org just know that you’re getting information straight from our people – what we want to tell Australians. It’s a direct dialogue to Australians for us. That is a really practical, grassroots thing to do.

There’s a process that will start in December that requires Australians to engage with the model of a voice to Parliament, and we’re going to ask people to make a submission.

We really want Australians to write a message from their heart about why an enshrined voice is important and why the government needs to do that. We’ll provide more information via that website so you can hear what it is that the dialogues want.

“Everybody is empowered and has agency as an individual Australian and voter to do that.”

People taking the time to meaningfully contribute is more important than a pro-forma submission. I know people are busy but this is one really pragmatic step that we ask people to take because this will swing it and say to Morrison, Australians want the referendum.

We also urge people to write to your member of Parliament and go to their local electorate offices to talk to their local member. That has had a massive impact. Because when politicians come back from their break that’s what they talk about. What was the sentiment in the office? What are the electorate talking to you about? Everybody is empowered and has agency as an individual Australian and voter to do that.

Contributors: Suzie Riddell & Professor Megan Davis

For more information and to sign up to support the Uluru Statement and be part of the dialogue led by the Uluru Statement leadership, go to https://ulurustatement.org/