Restoring the balance of power

Exploring what is required of non-Indigenous executives who hold positions of power in First Nations organisations.

- There is a long history across Australia of non-Indigenous executives managing First Nations organisations and reporting to First Nations

- In this cross-cultural context, it can be difficult to achieve an appropriate balance of power.

- Brendan Ferguson, an SVA Consulting Director, reflects on his experience as Interim CEO of a Yolŋu organisation, Aboriginal Resource Development Services (ARDS) Aboriginal Corporation, based in Darwin and Nhulunbuy.

- With input from Gawura Wanambi and Ben Grimes, the Chair and current CEO of ARDS respectively, Brendan identifies five qualities that are important for a non-Indigenous executive to possess if they are to manage a Yolŋu organisation and work successfully with Yolŋu.

This article was written with input from Gawura Wanambi, Chair, and Ben Grimes, CEO, ARDS Aboriginal Corporation.

Through the 2020 refresh of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, Australia’s federal, state and territory governments were pushed by the Coalition of Peaks1 to consider how they expected to achieve the targets that they were collectively setting. The Agreement is grounded in a set of four ‘Priority Reforms’ to change the way governments work. The Priority Reforms are based on what First Nations people consistently say is needed to improve their people’s lives. They are more important than the targets themselves. They describe how we will do things differently and achieve a more appropriate balance of power between Australian governments and our First Nations peoples.

The first Priority Reform highlights the need to support First Nations governance and decision-making structures. The second Priority Reform identifies the need to build and strengthen the community-controlled sector to deliver services that meet the needs of First Nations people.

Implicit in the logic of these two Priority Reforms is the contention – for which there is a growing body of evidence – that community-controlled organisations will deliver better outcomes for First Nations people. They are grounded in the fundamental and incontrovertible principle of self-determination.

But what if the management of a community-controlled organisation is largely undertaken by non-Indigenous people. What if it is balanda, or kartiya, or gubba, who often hold the balance of power within Aboriginal community-controlled organisations?2

There is a long history across Australia of non-Indigenous executives managing First Nations organisations and reporting to First Nations boards. There are reasons why this has historically been the case and why this will continue to be the case for some time in certain settings.

Foreign systems have been imposed on First Nations people through the process of colonisation. Three tiers of government have been established with a complex web of responsibilities and funding arrangements. Corporations laws, regulations and norms have been created with expectations in relation to governance and management that often conflict with traditional governance systems. In a remote and very remote context, where cultural and linguistic barriers are most significant, there remains a pervasive assumption (right or wrong) that First Nations boards will need support from non-Indigenous executives to navigate these systems through the day-to-day management of their organisations.

I am a non-Indigenous man, born and raised in Melbourne and now living in Darwin. Over the past eight years, I have worked as a consultant at Social Ventures Australia alongside a number of First Nations community-controlled organisations and peak bodies. In 2020, I found myself working as the interim CEO of an Aboriginal Corporation. I was one of those non-Indigenous executives.

Aboriginal Resource Development Services (ARDS) Aboriginal Corporation is a Yolŋu organisation operating across two offices in Nhulunbuy, north-east Arnhem Land, and Darwin in the Northern Territory. ARDS has a vision that First Nations people – particularly Yolŋu – are able to engage on equal terms with the wider Australian society and its organisations and systems.

To achieve that vision, ARDS works through creative media, community development, language and translation work and research and policy development to span the gap that often exists between the information that non-Indigenous services typically share, and the information First Nations communities want and need.

Like many non-profits across Australia, ARDS was heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged when ARDS was between CEOs. Through existing relationships in the east Arnhem region, I was asked by the board to support ARDS during this period, and agreed to take on the role of Interim CEO until a permanent CEO could be identified. For eight months, I worked closely with the Chair, Gawura Wanambi, in an effort to strengthen the organisation, before the board appointed Ben Grimes as ARDS’s permanent CEO.3

It is important to clarify that my experience should be confined to that of working with Yolŋu in north-east Arnhem land. While some of the messages in this article may resonate with non-Indigenous executives working with First Nations communities and organisations in other parts of Australia, this article does not pre-suppose a common, pan-Indigenous experience.

This experience led me to reflect on what is required of balanda (non-Indigenous people) occupying positions of power in Yolŋu community-controlled organisations. To further inform my thinking, I spoke with Gawura Wanambi and Ben Grimes who drew from their experiences working at ARDS and with other Yolŋu organisations in east Arnhem, where the vast majority of executives are balanda.

Principles of corporate governance tell us that the relationship between board and executive management is critical for good governance and organisational effectiveness, with each heavily reliant on the other. The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) describes this mutual dependence in the following terms:4

The board expects management to accept that the board’s role is to monitor and question, probe issues, seek clarification, offer insight and share its knowledge and experience. With management much more deeply involved in the detail and operations of the organisation, board members rely on management to share in a timely manner all material information needed for decision making to allow them to effectively fulfil their obligations as directors. The board also expects management to ask advice and make use of the directors’ wealth of experience as and when appropriate.

This balance can be delicate, and in the cross-cultural context with which we are concerned, the balance of power can skew heavily towards the balanda executive.

“Yolŋu directors often prefer to shepherd a balanda CEO in the right direction over a long period of time, rather than directly confronting or questioning.”

The CEO typically manages the flow of information and this is almost always produced in written form and in English. Management often controls the setting in which board meetings take place, for example, whether the meetings are held in English or with an interpreter and the time reserved for discussion of critical issues.

A misalignment of expectations can also occur in other, more subtle ways. The AICD’s articulation of the board’s role is manifestly interrogative, maintaining hard boundaries around the activities and conduct of management. Yolŋu directors typically adopt a different style. Ben explains that in his experience, “Yolŋu directors often prefer to shepherd a balanda CEO in the right direction over a long period of time, rather than directly confronting or questioning”. This style can provide the foundations for a relationship of great trust and respect, but it can also leave the board vulnerable to a balanda CEO who may push the boundaries of their responsibility.

Beyond the board, one might look to the regulatory framework for safeguards, but the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (the CATSI Act) does little to create accountability for management. The Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) – the regulatory body responsible for administering the CATSI Act – states that it “has no authority to censure a CEO, or to monitor their performance. Only directors do.”5

“… a CEO must be personally secure enough not to pursue signs of ‘success’ that may not be relevant or appropriate.”

Much rests, then, on the qualities that a balanda executive brings to the role if they are to be successful within a Yolŋu organisation. In considering those qualities, it is also important to recognise that ‘success’ may look quite different for a balanda executive at a Yolŋu organisation when compared to their peers in a mainstream organisation, particularly at CEO level. Ben observes that, “a CEO must be personally secure enough not to pursue signs of ‘success’ that may not be relevant or appropriate.

For instance, delivering a project within budget is not a good outcome if Yolŋu staff have not been instrumental in leading that work and given the opportunity to develop their skills in the process. That said, the CEO cannot hide behind these nuances and provide sub-par management, simply because they are working for an Aboriginal organisation. Managing this tension can be a daily struggle.”

Through discussion, Gawura, Ben and I identified five important qualities that we think would help a balanda executive to be successful in a Yolŋu organisation:

- A strong ethical framework and an unwavering commitment to act in a manner that is consistent with that framework: Recognising that there are few external safeguards, the candidate must be very clear about why they are in the role and who they are committed to serving. There must be a strong commitment to act with restraint to make sure that the balance of power does not shift away from the board and to the CEO. If their actions ever undermine that commitment, they need to be able to recognise this and correct their course. On my first day working at ARDS, Gawura explained my role as that of the djuŋgaya; not the boss, but the caretaker. A trusted and skilled agent of the Yolŋu board and members who owned the organisation. Understanding this role and who you work for can be helpful when navigating the tension that Ben describes above in relation to defining success.

- An advanced level of cultural capability: This quality extends well beyond the completion of generic cultural competence training, but requires a deep appreciation of the relevant people’s history, country, culture, language and law. For Yolŋu, this starts with learning about gurruṯu, a sophisticated system that defines interconnected relationships between all elements of the Yolŋu world. For balanda, who have not been raised with this world view, this learning is a critical part of the role, not just an add-on. During my time in the role at ARDS, I only scratched the surface of Yolŋu cultural competence and it represented my greatest development need.

- Strong mainstream management skills: Non-Indigenous executives are often appointed to First Nations organisations to help them navigate a foreign system. There is an assumption that the candidate brings strong mainstream management skills, which can complement the extensive cultural knowledge of a First Nations Chair and board. And yet, it is surprising how many non-Indigenous CEOs display remarkable ineptitude, which is not always immediately apparent to the board. This is particularly evident in less competitive, very remote settings, where non-Indigenous CEOs are often appointed on the strength of their prior relationship with directors. Perhaps because of the worldview that underpins gurrutu, Yolŋu directors often tend to preference candidates who are known to them, without a rigorous assessment of the candidate’s skills. Gawura comments that, “when we (the directors) don’t understand all of the things that a CEO does as part of the CEO job, it is very hard for us to choose the right person for that job.”

- An ability to create space: A candidate must be prepared to work proactively, every day, to create the conditions in which Yolŋu directors and staff can hold and wield power. This is often about how meetings are organised and run or how information is shared and perspectives canvassed. It is time-consuming to do this properly. It takes a lot of deliberate effort to avoid slipping into easy, bad habits or getting complacent, particularly if Yolŋu directors and staff have been conditioned to work in a particular way through the poor practices of past management. But it is essential to empowering Yolŋu to shape their organisation.

- Promotion of First Nations leadership: Finally, a candidate must also be proactive in promoting Yolŋu leadership at all levels of management, creating the pathway for Yolŋu leaders to take on executive responsibilities, over a timeframe that is appropriate for that community and organisation and in a way that doesn’t set them up to fail. This work is time-consuming and costly and often conflicts with other priorities, but it must be treated as essential. Balancing short term organisational goals with long-term staff development is a key component to developing leadership.

There are many benefits of a strong partnership between an engaged Yolŋu board and an effective balanda executive team in possession of these qualities. When it works, such a partnership – as described by Gawura above – can be formidable, enabling an organisation to represent the interests of, and deliver outcomes for, community members, whilst also meeting and exceeding the expectations of mainstream partners and funders.

But in a world where Yolŋu are truly empowered, their organisations would not be so reliant on balanda management. And the same can be said of First Nations people across Australia. On-going investment is required in mentoring, training and capacity building support, to build the next generation of First Nations managers and ensure that people can pursue those pathways.

The Martu Leadership Program (MLP), delivered by Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) in the East Pilbara, Western Australia, aims to build the capacity of Martu to be capable leaders at the interface between the ‘whitefella’ and Martu worlds. Leveraging the success of KJ’s on-country programs, the MLP seeks to build foundational skills and knowledge to support Martu people in self-determination, growing a viable economy, engaging effectively with government and addressing entrenched social issues. Key focus areas include building governance and decision-making capacity, as well as understanding relevant mainstream concepts such as companies, native title, the criminal justice system, evaluation, and constitutional recognition. The program also focuses on supporting the ‘whitefella’ world to learn about the Martu experience, and how to effectively work together.

Back on Yolŋu country, Djalkiri Foundation Aboriginal Corporation (Djalkiri) is a community-led organisation – with a Yolŋu CEO, Rarrtjiwuy Melanie Herdman – that aims to support and ground emerging Yolŋu leaders in both-ways theory and practice. Djalkiri delivers the Success Through Employment Pathways (STEP) Program, in close partnership with Yolŋu elders, who have strong knowledge of both the Yolŋu and balanda worlds, and non-Indigenous mentors who can support emerging leaders to navigate the mainstream system.

These programs have demonstrated success (in the case of MLP) and great promise (in the case of the much newer, STEP) because they have been locally designed and are highly contextualised to reflect the experience of emerging Martu and Yolŋu leaders respectively. They seek to grapple with the structural barriers that have made it so difficult for First Nations people to thrive in two worlds and for which we are yet to fully solve.

The emergence of First Nations executives will take some time yet, particularly where cultural and linguistic barriers are most significant. And during that time, non-Indigenous managers will have roles to play in supporting First Nations organisations. But it is incumbent upon those people to fulfill that role with humility, reflecting the types of qualities identified in this article. For the mere existence of a First Nations board will not equate to self-determination, unless those who walk alongside them are willing and able to work with integrity and restraint, to support the board and make it so.

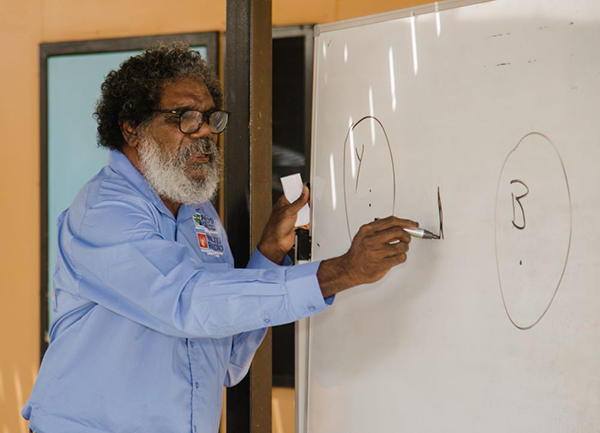

The illustration is of a Yolŋu Chair showing a non-Indigenous executive the layers of bark that can be peeled back from a paperbark tree using this as a metaphor for the layers of Yolŋu culture that are revealed to you when you show a willingness to learn.

1 The Coalition of Peaks is made up of over 50 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled peak and member organisations across Australia.

2 Balanda, kartiya and gubba are common terms used in Aboriginal languages in different parts of Australia to refer to non-Indigenous people. Balanda is commonly used across Arnhem land in Yolŋu communities.

3 See further in the SVA Annual Review, 2020-21, at pages 30-31.

4 Australian Institute of Company Directors, Director Tools: Relationship between the board and management, accessed on 22 January 2022.

5 ORIC Oracle, May 2018, CEO Accountability, accessed on 22 January 2022.

Author: Brendan Ferguson

With input from: Gawura Wanambi, Chair, ARDS Aboriginal Corporation and Ben Grimes, CEO, ARDS Aboriginal Corporation